The murder of 15-year-old Yeshiva student Chaim Weiss on Halloween, October 31/November 1, 1986 is still listed as "unsolved". Chaim had been a student at the Yeshiva School of Long Beach, 205 Beech Street Long Island, New York for going on three years.

The school was known as Mesivta Torah to students and faculty and is a branch of Beth Medrash Govoha in Lakewood, New Jersey, an affiliate of Agudath Israel of America. Chaim Weiss was raised in Staten Island, NY.

Chaim was hacked to death by a hatchet or similar weapon sometime between 1:25 AM and 7:30 AM November 1, 1986, when his body was found. He was struck viciously in his face/skull/neck, so viciously that it nearly severed his spinal cord, killing him instantly. When his absence was noted at morning prayers, at approximately 7:30 to 7:45, a dorm supervisor went upstairs to check on Chaim, who was known to have had the flu and a sore throat, when his body was discovered.

The New York Times reported a heavy knife was found within a few blocks of the murder, but it turned out to NOT be the murder weapon.

The Medical Examiner's Autopsy Report gave the cause of death as bludgeoning by a hatchet like weapon, probably because of the extensive damage to the victim's skull (a doctor compared it to a broken eggshell), Chaim was found to have multiple stab wounds on the right side of his head, neck and face, with lacerations of the brain. The first blow, which struck his right temple and penetrated his brain, had been sufficient to cause instant death. This probably, depending on how Chaim's head was resting on his pillow, showed that the perpetrator was right-handed.

The medical examiner described the murder as a "frenzy-type killing," which seems inexplicable given Chaim's modest life and his apparent popularity with other students. There is a general rule among law enforcement, with very few exceptions, mostly connected to mental illness, that the more vicious and bloody an attack is, the more likely it was done by someone who knew the victim and that the attack was deeply personal. In the FBI profile, done years later, faculty members describe him as "the brightest of the bright," while students saw him as popular and generous, but someone who had a "sharp tongue," which could have been a factor in his death, according to the report.

I do NOT believe this smear of Chaim by Rabbi Pitter, as with a lot of what was said by Yeshiva officials, conveniently, after the fact, I just naturally assume this is Yeshiva Rabbis/Officials' CYA, Cover Your Ass, crap. Like Chaim's father said, nothing bad or any other criticism was reported to him or his wife from the school until after Chaim was murdered.

Because the police got no further useful help from the inhabitants of the Yeshiva Dorm, there is no definite timeline. A crime scene detective had a different take on what happened. "In all probability, the offender would have had to have been close enough, geographically, to know that Weiss' body had not been discovered before returning to the scene . . . Upon re-entry, the assailant found the room dark and raised the shade to provide additional light . . . Weiss' body was moved by the assailant, either to provide easier access to the window and shade or for the assailant to look under the body for anything incriminating left there. The window may have been opened by the assailant to discard some item out the window, which he later retrieved."

I am not sure what to make of this detective's theory. I doubt once the perpetrator left, he would come back under any circumstances, unless he knew he left something behind. To return to the crime scene would take nerves of steel and a cold-blooded nature. If he was stuck waiting for his getaway, he may have been struck with remorse while waiting in the same room with a dead child's body, his victim, the 45 minutes that police believe he was in the room, while looking for a clear hallway and a clean escape. That may be one explanation for the child killer choosing to open the window and moving Chaim's body in accordance with Hasidic belief to alleviate some of his guilt for murdering an innocent child.

I suspect he remained for an extended period of time in Chaim's dorm room to figure out what to do next, how to make a clean getaway, make sure he left no evidence, removing any traces on his person, thinking up an alibi, if needed, and figuring out how to cover up and obscure any possible tie between him and Chaim. A logical assumption, after one of the boys on the floor had gotten up to pee twice during the night walking a few feet from Chaim's dorm room, he could not leave. If this boy had been spotted on the way to the bathroom by Chaim's murderer, while peering out of Chaim's door, he knew he would have to wait until the boy was back in his dorm room and given enough time to fall asleep again. This might also explain the door which was found open twice, the room of the peeing boy, even though his roommate said he got up twice to shut it.

The last time Chaim was seen alive was the morning of November 1st, when he was seen by classmate Chaim Goldberg, who saw him sitting in their 3rd floor dorm hallway reading a book between 12:45 and 1:25 AM. A religious rule required members to not turn on lights during the Sabbath, Saturday, but fire regulations required hallway lights to be on at all times. Chaim Goldberg also said whoever killed him must have been looking for him as a specific target because the perpetrator had to bypass other 37 other boys in 19 other dorm rooms, dorm monitors, student activity rooms, communal bathrooms, two flights of stairs, then negotiate hallways, silently, to get to Chaim on the third floor. Chaim's dorm room was at the dead end of the hallway which ran the length of the building on the top floor.

NYPD concluded he had been attacked while he slept and that there was no break-in at the school. There were no locks on the boys rooms. Chaim's room was on the third floor of the school, he had a dorm room to himself, while all other boys, except one other boy, had a roommate. There was no fire escape outside Chaim's window, the only way to escape would have been to retrace his steps. Strangely, the window in his room was left open after the attack. Chaim was sick, he had a sore throat/flu for which he was taking a prescription anti-viral medication, proving, I think, convincingly, that he would have never left the window open himself. The temperature at LaGuardia Airport was in the high 30's that night, while most of New York was in the low to mid 40's. It is believed in Hasidim faith, according to one source, that windows should be left open in a room containing a dead follower's body, to allow his soul to escape from from earthly bonds.

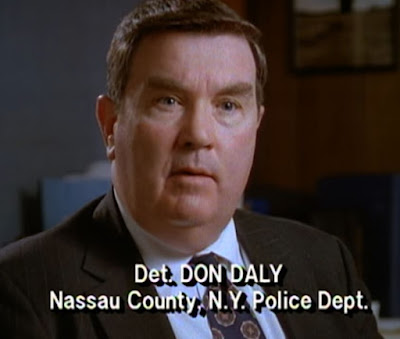

The NYPD Detectives, led by Detective Don Daly of the Nassau Police Department, were notified at 7:45 AM of the crime and arrived within minutes by 8 AM. Detectives immediately determined the Yeshiva had tight security and there were no signs of a break-in. Chaim had been sleeping face up in his bed when he was attacked, leaving a large pool of blood on his pillow. then someone dragged him to the floor, creating a second pool of blood, then his body was moved a third time, his feet and legs were raised and placed on his mattress, while his body remained on the floor, pointing towards the window. At this point, the third pool of blood was much smaller than the other two indicating, Chaim was probably already dead and that a great deal of time had expired since the attack. At some point the assailant opened Chaim's window.

Two odd things, Chaim was a great kid, who never got in trouble. These two things indicate something really bad happened to him at camp and that there may be a cover-up.

Chaim called his dad from a Hasidic Boys Camp five months prior, in July, crying and said he wanted to come home and desperately needed to talk to his dad about something which happened. He said he couldn't talk about it over the phone, he needed to do it in person. Dad may have assumed Chaim was homesick, though at 14, this was less than likely. That conversation never occurred because two things intervened, Chaim went to visit his grandparents for a couple of months in Europe and the family received a couple of phone calls from Rabbi Cooper, who DEMANDED to see Chaim the moment he got back. After meeting Rabbi Cooper alone, Chaim told his Dad that he did not want to discuss what they talked about or what had happened, so his dad never did learn what that phone call from camp was about, but he does remember how upset Chaim was and regrets not pressing his son to find out what bothered him.

While creating Columbo writers Levinson and Link interviewed LAPD officers to find the inside and out of being a detective. They even interviewed Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry who was a LAPD Officer for nearly 10 years before selling his first TV script. One thing these police officers were unanimous about, immediately suspect odd behavior or coincidences among people who know, are close to or are doing business with the victim in a murder investigation.

Levinson and Link in 1962 when they wrote the first Columbo Mystery: Prescription Murder. Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry, center, LAPD Officer 1955, immediately before he sold his first script.

In fact, the best reason to begin to suspect someone is that they have a too perfect alibi, they show arrogance or disdain for those trying to solve a crime, and/or they refuse to help solve a crime like this, the murder of an innocent boy, or have a too ready/convenient explanation for their own odd behavior or a coincidence.

EVERY ONE OF THOSE CONDITIONS HAS BEEN MET DURING THE INVESTIGATION OF THE MURDER OF INNOCENT 15-year-old Chaim Weiss!

No one with the school or camp can or has tried to explain Chaim's phone call to his dad. Chaim was a smart boy who was in serious emotional distress at camp because of something which happened. Then the meeting with his Rabbi which upset him almost as much. It is not an unreasonable assumption that what happened to Chaim at camp is tied to his meeting with Rabbi Cooper and then with what happened to him in his dorm room on one cold Halloween night in 1986.

In 1987, Detective John Nolan of the Nassau County PD said that "it's one of the toughest cases we've had, because we were never able to determine a motive. And without a motive, it's very tough to have direction.'' At the same time Captain John Azzata of Nassau PD said Chaim was the unlikeliest victim, having done nothing to warrant such an attack. And the fact that no one saw or heard anything in the quietest part of the night, when the crime was committed, is also deeply troubling.

The first step in any investigation is to look at the victim and his life for a reason for which he might have been killed. Chaim was a good kid, with no known vices, who took his education, at which he excelled, very seriously, spending hours daily studying/reading. He played sports enthusiastically, always displaying good sportsmanship. He was friends with all of his schoolmates, who all had impeccable reputations as well. They all liked Chaim, he had no known enemies and had never been bullied, having earned the nickname Bal Kiahron, which in Hebrew means "a person capable of understanding".

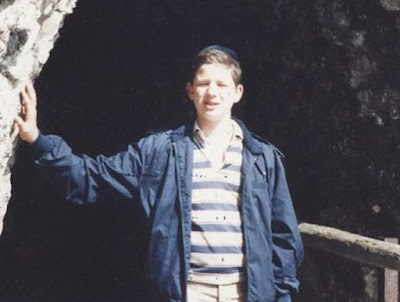

Chaim was born September 29, 1971 in Staten Island NY. His family lived in the Willowbrook neighborhood adjacent to the massive Willowbrook Park, which houses the Staten Island Public Library, Sports Center and Arts Center. He had a younger brother, Menachem, who was four years younger and a sister, Rachel, who was 7 years younger. They both adored their older brother who reciprocated the feeling.

In 2017, WPIX-TV NY did an update on the case, talking to Chaim's parents. At the end of camp Chaim visited his grandparents in Europe, who were Holocaust survivors, for several weeks. While he was in Europe, his mom and dad got two calls from Yeshiva head Rabbi Avram Cooper saying he MUST talk to Chaim immediately after he got back. It was very clear that this was NOT a request, it was a demand. The meeting occurred at Rabbi Cooper's home in Borough Park in Brooklyn immediately after Chaim's return, Chaim went into the house to speak to Rabbi Cooper, alone, per Rabbi Cooper's instructions, leaving his father in the car, Chaim spoke to the Rabbi for about 10 minutes. When Chaim came out of the house, his dad could tell Chaim was very upset, but Chaim said he didn't want to talk about it. His parents are heartbroken that they didn't press the issue to find out what was bothering their son.

No one has ever ascertained if anyone, rabbi, counselor, mentor or other boy was both at the camp and at the Yeshiva.

Now, for the second troubling incident, a boy who attended the Yeshiva 3 years after Chaim's death, said he was in the headmaster's office, incidentally, on another matter, when the rabbi had to leave. This boy saw a boy's hat on top of a tall filing cabinet, which put it out of easy reach. Curious about its odd placement, this boy went to look at it, picking it up he noticed the name Chaim Weiss was sown into the hat. A curious memento and odd that it was so prominently and anonymously displayed, without context. While you can't say with certainty whether it was some sort of "trophy," it is odd that it was kept in the headmaster's office and not, possibly, in some sort of memorial in the ground floor lobby of the building for the boys to honor their fallen brother.

There is one other possible clue. A hair was found on Chaim which is still in NYPD possession, but they were afraid testing it would destroy it. I hate the idea that someone gets away with a case like this, even if they have passed away the truth needs to come out.

Some relevant facts, which seem paramount, the perpetrator either came from inside of the facility or had a key to the building. Again, NYPD said there were NO signs of a break-in. This building would NOT be a target of sophisticated burglars. It was a Yeshiva occupied by religious high school students and everyone in the neighborhood and surrounding area knew that. There was NO treasure trove in this Yeshiva/School. The perpetrator left no clues, indicating some degree of sophistication and intelligence.

Next, since Chaim was attacked, slashed and hacked viciously in the face while he was SLEEPING, immediately killing him, it is not an unreasonable conclusion that he was the intended and only target. Chaim presented neither an immediate threat to the intruder, he did not interfere with or interrupt a burglary or block a perpetrator's entry or escape.

In fact, one boy, Eli Kushner, who was at the school on that night, says you could only end up in Chaim's dorm room if you were looking for it, it was at the opposite end the 3rd floor stairs, there was no fire escape, bathroom and his room was at the end of the hallway, your only choice, after commission of this crime, to escape, would be to retrace your steps.

There was no struggle, the attack on Chaim was immediate, vicious and targeted. This was not a burglar discovered in the commission of his crime, who killed to effect his escape.

This was a deliberate attack on one particular boy.

One boy living on the third floor remembers waking up a couple of times that night and noticing that his door was not completely shut. He remembers his roommate had gotten up a couple of times during the night to pee. He assumed his roommate had forgotten to shut it, so he got up and shut it, but noticed that the same thing happened again a few hours later. If the interloper, whether from outside or inside, had noticed his roommate, he might have checked to make sure he was asleep during his "escape". Choosing to close the door, but not shut it, engaging the catch which would have probably made a startling noise in the deathly quiet dorm, someone obviously did not want to be discovered. At the time, the boy who noticed the door was not shut and latched, just figured it was his roommate, a Rabbi or dorm monitor checking on the boys.

Since no weapon was found at the scene or on the premises and no one recalled any hatchet being located anywhere at the dorm grounds prior to the attack, the weapon must have been brought to the scene or bought by the perpetrator before hand and disposed of afterwards. This was in all probability a premeditated crime. A hatchet like weapon is an odd choice, hard to hide and yet much more likely to inflict a fatal wound immediately. A knife might require repeated strikes and might have resulted in a struggle with the victim before he succumbed.

I am convinced that someone, possibly more than one person, knew or had strong suspicions as to who killed Chaim and made a decision to cover-up the assailant's identity, possibly, because the perpetrator was their friend or to protect their faith or the Yeshiva/School, which obviously mattered more to them than one INNOCENT 15-year-old boy's life.

An FBI Profiler who was brought into the case believed that the murder was an inside job, by someone who knew Chaim well and had been a deliberate, purposeful act. The person who went to Chaim's dorm room that night, did so to kill him. I agree 100% with that conclusion. The profiler suggested that the act had been committed by someone close to Chaim's age, probably under 25-years-old.

In 1988, FBI Senior Profiler John Douglas said, on a show to mark the 100th anniversary of Jack the Ripper's murder spree, bloody crime scenes almost always exclude perpetrators who are over 30-years-old. People with criminal tendencies under 30 tend to be selfish and are indifferent to the suffering of their victims and being covered in blood would mean nothing to them. I don't know that I necessarily agree with that, considering the strange actions of all the adults involved afterwards. The best that can be said for the adults behavior, including several rabbis, is that they circled the wagons to protect the school, at the same time guaranteeing that the murderer was allowed to get away with his crime.

Police Detectives said the investigation was hampered by the reticence of the boys to provide any, even trivial/incidental information, almost like they were instructed not to cooperate. Just an impression police had.

While not conclusive, Rabbi Cooper's actions are beyond suspicious, even if he was not personally involved, an argument can be made that he knows far more, including possibly the actual perpetrator's identity or a suspicion to a most likely suspect, than he has ever admitted.

Police sources said that the investigation was hampered at every stage by intransigence of the staff and students at the facility to discuss the crime, or, at best, being minimally cooperative.

Detective Daly had several meetings with the boys and separately with staff and Rabbis, asking if they had noticed any suspicious behavior by anyone. But these questions were met with total silence.

Police suspected that this crime was personal based on how vicious the attack was and that Chaim was struck in the face. Most murders occur at a distance or from behind, in the case of strangling, so the assailant doesn't have to look in their victim's face as life drains from them, because the perpetrator doesn't want to make a personal connection with the victim and his suffering. The exception would be murder in anger or a professional or serial killers. But normal people driven to kill, for whatever reason, would normally not do this unless motivated by extreme anger/emotion/fear. Stabbings with a knife/hatchet and strangulation from the front, while looking at your victim, staring in his eyes/face, indicate these attacks are deeply personal and usually done in extreme hate/anger, you are looking at your victims face as you take their life. Another factor to consider was the amount of time the perpetrator spent in Chaim's room. Considering blood flow, the longest amount of time was 45 minutes. This is not someone who was troubled by what he did. This was a cold-blooded crime by a cold-blooded man/boy.

Rabbi Cooper told the family in the civil trial over Chaim's death, the family needed to reflect on their and Chaim's sinful deeds which may have brought such a fate upon them. I find that appalling. No one, much less an INNOCENT child, deserves to be murdered. A man of faith should comfort the suffering of a family which lost a child, not make it worse. Contacted in 2017 for the WPIX NY documentary, Rabbi Cooper told a NY WPIX Reporter "I am NOT interested in speaking". A strange choice of words. Not the far more appropriate response: I do not know anything beyond what I said at the time and I have nothing to add.

The $15,000,000 Civil Suit was dropped after a settlement was reached. Chaim's father said he was troubled at having to sue his religion, but he was angry that no one was cooperating with the investigation. After the murder, almost all the students tried to transfer to other religious schools. But a newspaper reported that a rabbinical council determined to refuse transfers to prevent the collapse of the Long Island Yeshiva.

https://youtube.com/watch?=8x_lljAiMvk

A young man/boy of indeterminate age was seen by a jogger on the beach near the pier sitting on a bench at about 7AM, 100 yards from the dorm that Saturday morning. There is no way to tell if his presence was connected to the crime or not. The young man/boy was NOT specificially identified as hasidic, but may have been.

If the staff, rabbis and boys were upset by the murder they may have forgotten anyone missing or acting strangely during the morning before discovering Chaim's body. I am sure there was near hysteria at the dorm afterwards, many turning to fervent prayer, oblivious to anything else. Only at the end of the Sabbath, sundown Saturday were the police allowed to talk to the boys, possible 17 to 20 hours after the murder could the crime be investigated, which was more than enough time for the Chaim's cold-blooded killer to cover-up and get away with his crime.

I want to address one theory which has gotten some play in analysis/reviews of Chaim's murder. Some people seem to believe that Chaim was having homosexual sex with a boy/counselor at camp and got "caught." Their theory is that this was the reason Chaim was so upset at camp. It is this which prompted him to call his dad in July.

If it had been a consensual relationship with another boy or counselor, then why would Chaim place a panicked phone call to his dad? He would want to be discrete and keep it secret, waiting until he was with his dad to have a heart to heart conversation. His silence would be met by silence, by the other male and the school, especially if the school wanted to cover it up too. There was no reason for Chaim's panicked phone call, if everyone wanted to cover-up whatever happened.

Just a feeling I have, I believe Chaim had a strong enough bond with and love for his dad that he COULD/WOULD talk to him about anything, even talking to him about a consensual experimental homosexual liaison, if such had been discovered at camp that summer. For this and the previous reason, I am almost 100% sure this is a canard, a false narrative, a LIE!!

I do not believe Chaim had any consensual sexual relationship with anyone, male or female, at camp. I believe, until proven otherwise, Chaim was a virgin by choice, at least until he was quite POSSIBLY attacked and sexually assaulted at that summer camp. Furthermore, Chaim nearly hysterical reaction to whatever happened to him, if a homosexual assault, would indicate that Chaim was heterosexual and a victim, not a consensual participant. Regardless, it must be remembered whoever caused this panicked phone call from Chaim is the only one who knows, plus any of his friends who helped cover up what happened. He and they silenced Chaim so we will never know the truth. This whole proposition is a ridiculous discussion and, I believe, a diversion to protect the perpetrator.

Beyond that, Chaim's private life and any consensual relationship with anyone of his choice is none of our business. Whether Chaim was straight or gay is irrelevant to what happened to him that morning of November 1, 1986.

But if someone older had taken advantage or forced themselves on him? Or if he had been the victim of some sort of sexually abusive hazing, both would have prompted a similar reaction in a naïve 14-year-old boy and a panicked phone call to his Dad. These are scenarios which fit the facts. Someone was pressuring Chaim to keep quiet. Afraid that he would eventually squeal, then this person would feel he would have to take action to silence him.

First, let me say, if Chaim was gay, it makes no difference to me. But Chaim's phone call and Rabbi Cooper's behavior don't ring true for a experimental/voluntary/consensual assignation scenario. One thing is certain, something happened to Chaim at camp. He wanted to talk to his dad about it, but he was scared or ashamed, or both. Boys tend to be ashamed after a sexual assault/hazing in which they are innocent victims, covering it up to the perpetrator's benefit.

"I used to work with a co-worker who did know Chaim Weiss. They were not close friends but did pray in the same temple. The co-worker is an attorney who flunked the bar like four times before passing, but he was very religious orthodox Jew. He was fluent in Hebrew, Yiddish, and could read the Babylonian Talmud in Aramaic. I don't think he would make up any story. One day we were talking about 1990's TV programs and I mentioned UM (UM/Unsolved Mysteries with Robert Stack did a segment on Chaim's murder) and he said he knew someone from the show.

Weiss was a bit older than him, but he said Weiss mom lived a few houses away. I don't know if UM mentioned anything about an autopsy? Usually forbidden, he said they made an exception for Weiss due to the nature of death. He told me that Weiss was in fact molested. Weiss mom really had a bad breakdown in the aftermath." From an unverified web posting.

If this post is accurate, then Chaim Weiss was murdered by the man/boy who assaulted/raped him in summer camp and then got away with both child assault/rape of a young teenage boy and his murder. That is horrific and a nightmare.

Seeing his mom and dad's devotion and emotional devastation to Chaim's death tells me he wanted to tell his dad and that he was NOT afraid of his dad. But then Rabbi Cooper COMMANDS Chaim to come to his house and see him immediately after his return from his grandparents. Suddenly Chaim drops the matter. Was Chaim afraid of Rabbi Cooper? Apparently. Chaim was NOT happy dropping the matter. He wanted to tell his dad, but Rabbi Cooper obviously said something to him which made it clear Rabbi Cooper did not want him telling his dad anything. What did Rabbi Cooper tell him? Was there any threat to Chaim's continued attendance at the Yeshiva, which meant so much to the 15-year-old boy?

Chaim was honored to be at the Yeshiva, his lifelong dream since he excelled at religious studies, academics and sports. He was extremely well liked by his teachers and other boys. It would destroy him to lose the dream that he had worked so hard to achieve.

I would be really curious to see what Rabbi Cooper told police about his conversation with Chaim when he got back from Europe. If Rabbi Cooper was angry/bothered by a possible consensual homosexual relationship involving Chaim, discovered at camp, then he would want to get rid of Chaim, not keep him in school. The logical thing would be to send a letter to Chaim's mom/dad telling them Chaim would not be invited back the next year. This did not happen, so I suspect a crisis rising from a voluntary relationship is the least likely scenario.

Two of the thirty-eight boys at the Yeshiva had rooms to themselves. Logic dictates, 36 boys slept in 18 dorm rooms with two boys per room, but two boys, including Chaim, slept in rooms designed for two boys, by themselves. Wouldn't it make more sense that these two boys should share a room together? Unless someone chose to keep these boys alone in a room by themselves by design?

Chaim did NOT want to talk to Rabbi Cooper. And Rabbi Cooper's words during the civil lawsuit could be interpreted as trying to intimidate them, telling the family to shut-up and drop the matter, telling them it was Chaim and/or your fault that your son is dead.

Shomrei Hada Funeral Home where Chaim Weiss Memorial Service was held. 1,000 people turned out for Chaim and his family.

South Brunswick, Middlesex County, New Jersey, USA

2) There was no sign of sexual abuse/attempted rape or burglary that night, the murderous attack was immediate and fatal. There were no signs of defensive wounds on Chaim. The room had NOT been rummaged through or left in disarray. You wouldn't know anything had happened other than the attack on Chaim who lay dead on the floor and the three pools of blood, one on his pillow and the other two on the floor. He was murdered directly from his sleep. These two facts establish that sex or greed were NOT the motive for the attack.

This was an ASSASSINATION, the pre-planned murder of an INNOCENT 15-year-old boy.

3) On its face, this is a motiveless crime. It is illogical for anyone to want to kill Chaim Weiss. He was a kid, in a closed, tightly controlled environment. It would be nearly impossible for him to misbehave or get in any serious trouble and he appears not to have done so. He had no enemies or run ins with anyone inside or outside the Yeshiva that anyone could recall. What reason could anyone have to kill this boy? Detective Daly believed find a motive and you've found the murderer.

4) Chaim's dorm room, in which he lived alone, was on the top floor at the front of the building, at the end of the 3rd floor hallway with no exit/fire escape, proving that Chaim was the target of the murderer. Why would anyone assume any of the boys bunked alone, unless they knew it going in. Why would they bypass all the other boys to get to Chaim? The criminal, if an outsider, would have had to risk discovery repeatedly before and after the murder bypassing every other occupant's door to get to him, then retracing his steps to the back of the building where the fire escape/stairs were. The fire escape was not pulled down to allow someone to enter and exit the building undetected, bypassing most of the boys.

5) Out of 38 boys living in the dorm which encompassed three floors, only two boys had rooms to themselves, which is odd on its face. If 36 boys lived in 2 bed dorm rooms with roommates, why would Chaim and one other boy live in 2 bed dorm rooms by themselves, instead of bunking together? They had been assigned rooms by themselves at the beginning of the school year, by one report, so their solitary sleeping condition was by design. While Chaim was an excellent student, almost every boy in the dorm excelled in their studies. What made 11th grader Chaim and this other boy special? The boys themselves were curious as to why these two boys had rooms to themselves. Having a roommate is a good growing up experience for a boy, especially for sheltered boys, teaching them how to cohabit and compromise with another person, build a possible friendship with a stranger and be more outgoing. Someone chose these two boys to have rooms by themselves, perhaps to isolate them.

6) The fact that the body was moved two times after the murder over an extended period of time, as evidenced by the three different pools of Chaim's blood, indicates that the murderer was in Chaim's room for an long period of time. This was not a burglar trying to disable someone to facilitate his crime or effect his escape. Something else was going on.

7) The choice of a "hatchet" to attack Chaim indicates the perpetrator wanted to kill him, which he did almost immediately. The savagery of the attack, striking him in the face/head indicates this was personal and done in either extreme anger or fear, because Chaim was a threat, perceived or real, to the perpetrator. Police call it overkill and it is almost always done by someone who knows their victim(s).

8) The use of a hatchet which was apparently brought/purchased/stolen for the purpose of killing Chaim, proves premeditation. The police inquiry found no tool like that in or around the dorm and the inhabitants had no recollection of any such weapon. The fact that the dorm is less than 100 yards from the Atlantic Ocean means disposing of the weapon would be incredibly easy.

9) All the support staff were interrogated relentlessly, including lie detector tests. Special police targets were non-Jewish janitors, food delivery service employees, maintenance staff, utility employees, even the newspaper delivery boy and mailman, who may have visited the dorm in the prior 2 years. The Polish Catholic janitor was interviewed a 2nd time in Poland. He had left the country after being interrogated and investigated thoroughly, passing a lie detector test and providing an airtight alibi. He was employed at a military base trying to earn citizenship, you are allowed to join the military with a green card, and was on site at the base when the crime occurred, so he was cleared by police.

Greencard Holders can become members of the US Military if:

1) Lawful GreenCard Holder. Reside in the US

2) Speak, read and write English fluently

3) Are physically fit

4) Submit a notarized copy of their GreenCard

5) Apply in Person

6) Pass the Medical Exam, Military Aptitude and IQ Test

7) Pass a Background check

8) Pass Basic Training

Members of the US Military are allowed to work for employers outside of their base, if:

1) The job is approved by their commanding officer

2) The job does not interfere with their military duties

3) Their employer passes a security check

The Yeshiva Janitor was in the US on a legitimate Green Card. He still retained his Polish citizenship, pending being granted American citizenship. His military record was excellent with no deficiencies or questionable aspects of any sort.

Police were satisfied that he had little or no contact with Chaim and no reason for any particular animus directed specifically at the boy. The boys generally liked the janitor, though they occasionally verbally jousted with him. The feeling and jousting was reciprocated.

After the thorough and rigorous investigation, the janitor was cleared, but he chose to go home to Poland and gave up on trying to become an American Citizen because of the murder and suspicion which it aroused. He has since passed away.

Now, for the zinger: Yeshiva sources suggested the janitor bribed his commanding officer and/or the base checkpoint guards, then stole a vehicle to commit the murder of a 15-year-old boy he hardly knew and had no logical reason to kill, then returned to his base undetected.

There is a rule of conspiracies, the bigger the conspiracy, the more people involved, the less likely it is to succeed. And with any crime orchestrated by someone of average or above average inteilligence, a conspiracy is not the solution you are looking for. If you commit a crime by yourself, then you don't have to worry about the loyalty of a co-conspirator. And where the hell is a janitor supposed to get the money to bribe anyone. This theory is totally ridiculous and FALSE.

10) A 10-year-old Jewish boy who lived near the dorm and was friendly with the boys and a frequent guest to the building, said police talked to him once and told his parents that there was nothing to worry about, they were 90% sure it was an inside job, but it might be better if he avoided the Yeshiva, students, faculty and Rabbis until the investigation was complete.

11) Opening the window of Chaim's room after the murderer, indicates the murderer was probably Hasidic as well. We know Chaim was sick, he had the flu and a sore throat, and would have never have opened it himself. The temperature was mid to low 40's on November 1, 1986. The murderer opened that window. For a non-Hasidic murderer to have done this as some sort of misdirection, implies a person with the sophistication of Sherlock Holmes with the menace and degenerate mind of Moriarity. This is a canard. According to a source, a window is left open after a death so the dead can escape his body and earthly bounds, which is a part of their religious tradition.

12) Chaim's body was discovered at just after 7:30 AM on Saturday, after Chaim missed morning prayers. Police were notified within minutes, but after arriving they were somewhat surprised that they received no cooperation, no interviews, no questions answered, until after sundown that night, per Hasidic religious belief, which demanded/required prayers be the only activity allowed for adherents from sunrise to sundown on the Sabbath.

The boys lit a traditional YAHZREIT 7 day candle to honor their fallen schoolmate, which police noticed upon their arrival. Immediately after arriving Saturday morning, the police assumed control of Chaim's dorm room, taping it off, preventing anyone from entering. But, somehow, somebody entered Chaim's room after they taped it off and lit a 2nd candle. No one claimed credit or responsibility. When questioned, even after a promise of no repercussions, no one admitted placing and lighting the second candle.

"My grandfather worked on this case. The reason no one saw the candle placed was because the person who was supposed to be watching fell asleep. When my grandfather first saw the body, and he said in his own words, “he was an absolute mess”. Multiple stab wounds. The worst wounds being on his head."

Isn't it odd that someone would sneak by a sleeping policeman to place a 2nd candle in a dead boy's room?

13) A mentally ill man/drifter who was familiar to everyone in the neighborhood, including beat cops, was momentarily seen as a possible suspect. But he was never known to be violent or threatening and had never shown any animus to the boys at the Yeshiva. He was observed to be clumsy and disorganized by people in the neighborhood. He was an older man in his 50's, probably not in the best of health and lacking agility and physical strength. Though I haven't read it anywhere, he was probably alcoholic or on drugs.

He was never seen with any sort of weapon, certainly not a hatchet/knife. Since it was not a burglary/robbery and no sexual assault occurred, the only logical alternative, other than a personal attack on Chaim, was a mentally ill well organized killer/serial killer, like Ted Bundy, which this man was not. But even the mentally ill have motives. This suspicion didn't make sense. This was a cold-blooded, determined, calculated, well executed crime. Since police suspected a high level of competence and intelligence as well as nerves of steel in the commission of this crime, this mentally ill man was quickly dismissed as a suspect.

14) Since this was Halloween night, a community police officer had been assigned to the dorm to prevent any provocative incidents or shenanigans, escorting the boys to and from the facility and its campus until midnight, according to one report. The officer was interviewed as to whether he noticed anything out of the ordinary that night. He did not. He was also asked if he had noticed any strangers in the vicinity. Again, he did not. The officer had been assigned to the dorm and boys because of some mild catcalling by local teens in the past, but never anything more serious than that.

This was NOT a Halloween prank by a teenager gone bad/wrong.

15) The young man/boy spotted by the jogger at 7 AM on a bench near the pier/ocean on the morning of the murder raises one interesting question. Since security was tight at the dorm, heightened because of Halloween, anyone, a boy/staff member, leaving campus would have been noticed leaving or having to be readmitted to the building. No one reported anyone leaving campus and coming back the morning Chaim's murder was discovered, certainly not after boys/staff began waking up at 5 AM.

It must be remembered all of the boys entering and exiting the dorm were governed/admitted by staff, but no one recorded or needed to admit staff/rabbis who had their own keys and could enter and leave 24/7, undetected, at will.

Police could not track down anyone from the dorm or inside the local community who might have been this person. Chances are it was just a coincidence.

But then again, maybe not. In the confusion after Chaim's body was found it would be a perfect time to dispose of the weapon, if the perpetrator had not been able to sneak out and back in earlier, he could then. There were people with keys, staff/rabbis/mentors who could have done so unnoticed before anyone woke up. I have been unable to determine whether any of the boys were given keys which might explain the boy/man on the bench on the beach by the Atlantic Ocean.

16) Police never felt they received much, if any, support/cooperation from religious staff, dorm staff and the boys. Nassau County Detective Daly held meetings with the boys seeking any clue, suspicion, any odd occurrence, strange behavior, no matter how trivial, plus any possible theories the boys themselves might have, but he was always met with total silence. He deduced it may have been based on their religious belief that no accusation can be made without 100% proof. A cynic might suspect the boys were ordered/encouraged to maintain silence to protect their Yeshiva, Religion, Rabbis and/or their Hasidic community. Not that any of the boys may have thought any particular person/boy participated in or had knowledge of the crime, but the staff, including rabbis, may have reinforced this behavior by having told the boys to circle the wagons, to protect their faith and co-religionists.

A lie detector test was administered to almost everyone involved. A few parents objected and their sons were investigated without one and cleared. While most of the staff and boys passed their lie detector tests with "flying colors," no one tested as obviously lying, but a few of the adults/boys gave answers which tested "inconclusive". Normally, this means the person is high strung and was experiencing too much stress to test clearly.

One other thing to remember, a sociopath/psychopath would be able to lie with impunity and probably pass a lie detector test easily, because they never feel guilt and do not possess a conscience. It is horrifying to think such a predator could exist undetected in such an environment as this.

At every step for detectives, fog enveloped the investigation, which, of course, protected the murderer, whether incidentally or deliberately.

17) Evidence indicates this was an inside job by someone who worked, lived in or had access to the dorm building currently or at some point in the past. And they quite possibly had a key, either currently issued or their own secretly made copy. Or they were already in the building when the crime occurred. Because of this, police looked to motive, why someone might have murdered Chaim.

18) Some of the School's Rabbis and Administrators have argued for 38 years that the Polish Janitor committed the crime after the murder. No one, staff, rabbis or boys had anything bad to say about the janitor before the murder. His employee evaluations were always positive. He passed a lie detector test easily. According to one source, he also had a rock solid alibi.

Police were convinced that he was a convenient suspect for the school administrators to shift the blame and focus of the investigation after the murder.

Police logic was the odd positioning of Chaim's body, moved TWO TIMES and opening the window in accordance with Hasidim belief are the things which convinced police that the murderer was a member of the school's faith. If it was deliberate misdirection by the school/staff, does that mean that they know who did it? That question must be asked.

The same officials offer blanket denials of any student or staff member committing this crime. These same officials also speculated a door lock was defective, which police were unable to verify at the time. All locks were checked by police and worked perfectly. Earlier Halloween night they had been checked by the community police officer assigned to the dorm. He verified there was NOTHING wrong with any of the dorm's locks.

Up front, to say that there was a broken lock, when there wasn't, merely muddies the water and leads no where.

19) A boy had committed suicide inside the dorm boys bathroom a couple of years before. He was 13-years-old and hanged himself. The school said the boy was depressed and left it at that. There was whispering among the boys at the time, and since, that there was more to the story, but that proposition was/is suppressed by the school.

The question must be asked, was this boy too the victim of rape/sexual assault, with the rapist taking care to drive the boy to commit suicide, through guilt, fear or intimidation, to make sure the boy would never testify against him? And who would have the power and influence to drive a boy to commit suicide. Additionally, what if this boy was murdered and his death was made to look like suicide? Benefitting from the school circling the wagons, protecting both the school and the murderer. And horrifically, what if this was the same person who murdered Chaim Weiss?

The only thing which should have mattered to everyone involved in this case should have been catching the person who did this to an innocent 15-year-old boy. It is obvious that that did not happen. Each and every person who obstructed this case, whatever their motivation, is at least partially responsible for the murderer of Chaim Weiss getting away with murder.

Finally, this was posted anonymously on a memorial page for Chaim Weiss. Take it for what it is worth. It is a story about a boy who went to the same school as Chaim who had a very bad experience with an alumnus. Click on it to enlarge the post and read it.

20) I went on an Orthodox website/forum which had a discussion about Chaim Weiss's murder. These posts depressed me.

It isn't as rare as you might think:

Dozier Reform School in Evangelical Bible Belt Florida

We've all heard sex scandals about Catholic Priests, but that is only the tip of the iceberg. I don't think I ever heard anything like this about the Jewish Faith until about 2010 when I read a story about an Orthodox Jewish Boys Camp and sexual abuse of 100's of boys. Then I heard a story of Evangelicals torturing, sexually abusing and raping 1000's of boys for over 100 years at Evangelical Bible Belt Florida Dozier Reform School/Boys Prison, in Marianna Florida, along the Alabama/Georgia border. In a 2009 US Justice Department investigation, which led to Dozier being shut down and sold in 2012, 100 years of beatings, torture, rape and sexual abuse were spelled out and confirmed. Almost 100 boys graves were discovered by construction crews in 2012. Almost every boys' body showed signs of torture by these Evangelical "christian" guards/staff. Since then there was a huge scandal in the Mormon Church and the Boy Scouts. Several Assemblies of God teachers at their private schools have been accused of sexually abusing boys and girls.

A News Story from the Guardian Newspaper UK from 2013 about how victims of sexual abuse in Brooklyn's Orthodox Community who couldn't get any help from local DA's or their Rabbinical Council.

My Nana taught me that people who go into religion either do it for very good or very bad reasons. Her 13-year-old best friend was raped by her Southern Baptist preacher when she was a kid. She and her family left the church. Apparently, she was 100% right.

A huge scandal, accusations against over 100 Southern Baptist Preachers, who had raped/molested at least 700 known victims and possibly 1000's of boys/girls, many who never came forward, hit the Southern Baptist Convention in 2019, which was only discovered after one newspaper The Houston Chronicle, did a serious investigation in response to rumors which had been whispered for years, including accusations against the President of the Southern Baptist Convention and head of the Church. Evangelicals and Republicans repeatedly tried to stop the reporters and the story. The reason this is so noteworthy, Southern Baptists are almost always the first to accuse, point fingers at and attack others. https://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/investigations/article/Southern-Baptist-sexual-abuse-spreads-as-leaders-13588038.php

First, the Polish Catholic Janitor was accused repeatedly of being the murderer with a certainty and without evidence, which scares me. This echoes the Yeshiva staff's unproven, without foundation, accusations, which some police officers suspect was designed to divert suspicion.

The janitor is the one person who had an ironclad alibi provided by his US Army Base, its staff and his commanding officers. These US Army Officers would have no reason to lie or defend him if he was guilty. They would certainly want to get rid of this janitor if he was guilty. This accusation is 100% FRAUDULENT!

The next most popular suspect, a disgruntled business associate, possibly a Mafia member, of his dad, Anton Weiss, who had lost money on a business deal and sent agents to kill Chaim in revenge. The Mafia has never been known to murder children or wives. If they had an issue with dad, they would take it up with him. Also this accusation was offered without any proof. This accusation has no basis in fact and is 100% FRAUDULENT!

Another accusation: it was implied dad was having an inappropriate relationship with his son, a baseless accusation of which I am horrifically appalled. I am assuming this is a part of the orchestrated cover-up and campaign to get Chaim's family to shut-up. Losing their son broke this family's hearts. Again, this is offered with absolutely no proof and is an incredibly cruel lie. This accusation has no basis in fact and is 100% FRAUDULENT!

One consistent thread through 80% of the posts, the boys/staff/rabbis were 100% innocent, regardless of the evidence or what the investigation turns up, and they don't need to prove a damn thing and should never have been suspected or bothered by detectives: their word was good enough.

If it isn't good enough for a poor kid, a black kid, a white kid from a trailer park, then it isn't good enough for the Yeshiva staff and boys either.

Yes, they should be questioned, as should the janitor, the mailman, the paper boy, the mentally ill homeless man, etc. A boy, an innocent child, was VICIOUSLY MURDERED and that should matter to any decent human being, regardless of religion or politics.

The person certain to never solve a crime is the person who tells you who can't be the criminal based on no evidence or proof, only on their built in prejudice.

A few of the forum posters agree with me and my analysis and ask the same questions I have asked on this page

I will add one hopeful note, one alumnus of the Yeshiva, a classmate of Chaim's, said they all miss their friend, talk about the case all the time and have their own favorite suspects. Bringing the murderer to justice is important to them. They too believe it was an inside job. He said they have made progress and feel they have a better grasp of the case than anyone other than the police. I wish them success and think Chaim would be particularly proud if one of them solved his murder.

Requiescat in Pace, pal.

Murder Most Foul, Four Dutch Juvenile Delinquents commit petty crimes which eventualy led to MURDER

In the early 1970's when I was a teenager, I read about a Dutch case from 1960. It was made into a movie in 2008 called Bloedbroeders. Three bored boys, two very rich brothers, 16 and 14 1/2, Boudewijn and Ewout Henny and and 15-year-old friend Hennie Workhoven, joined by young career juvenile delinquent Theo Mastwijk (14), committed a series of petty crimes like shoplifting and joy riding/stealing bikes/motorcycles.

The police got so fed up with the crime wave that they made a concerted effort to catch and prosecute the perpetrators. They zeroed in on the underage career juvenile delinquent Theo Mastwijik, pulling him in for questioning and then his friends.

Because of the harassment and pressure from police detectives, Theo went to the two brothers at their palatial home and demanded that they hide him, so the brothers hid him in their home's attic cupola. This went on for weeks. The brothers had to feed him and carry a bucket, his toilet, out daily. Needless to say, they eventually begged him to flee the jurisdiction or turn himself in, keeping his mouth shut, to protect his buddies. He refused to do either and demanded a huge amount of money, which the brothers did not have, before he would flee. Finally all three boys decided that he must be terminated.

The body of Theo Mastwijk was coincidentally discovered by a family maintenance employee on Friday 27 October 1961 doing a repair on the septic tank. Theo's body was covered with whitewash/quick lime. After investigation, police determined Theo had been killed in June 1960. Identification was determined because remnants of the shirt he had been wearing for his juvenile mug shot were found with his remains.

The three boys, by then 18/17 and 16-years-old, mug shots were taken almost a year and a half after the crime, so they were much younger looking when the crime occurred. This is reflected in casting for the movie.

The murder case was being talked about all over the country, because the murderers were rich kids. Boudewijn and Ewout were the sons of the director and largest stockholder of an insurance company.

The brothers were allowed out of jail for sailing regattas and camping trips with family and friends while awaiting trial

Boudewijn (Arnout in the film) and Hennie Werkhoven (Simon in the film) were convicted and sentenced to nine years of jail in 1963. The judge thought Ewout (Victor in the film) was involved with the murder as well and he was sent to jail for six years.

Boudewijn managed to escape, but was immediately recaptured.

In 2008 during the Bush Crash their inherited insurance company went bankrupt and the brothers lost everything.

THE MOST EXPENSIVE SPORTS PHOTO OF ALL TIME.

The photo is of Charlie Bowdre and Manuela Herrera wedding reception guests in front of the Trunstall cabin playing croquet in 1878. One of the guests, leaning on his Croquet Mallet is Billy "The Kid" McCarty with his friend Tom O'Folliard. O'Folliard was born in Uvalde Texas. He was of French ancestry and his family name was Folliard. Like Mafia Don Frank Castiglia who changed his name to Costello and comedian Lou Cristillo who changed his name to Costello too, both figuring that an Irish name sounded more American. Notice the "Kid's" knitted sweater, you can see his revolvers outline at belt level through his sweater. The Billy the Kid photo where he is holding a gun sold for $2.3 MILLION DOLLARS. The Billy the Kid photo playing Croquet was bought for $2 in a thrift store in Fresno California.

The Most Expensive Piece of Sports Memorbilia of all Time, from a True American Hero