The Cleveland Street Scandal

Rich Powerful Adults and connected Pimps committed the crime, but it was the kids who went to prison at hard labor. Victorian England was no paradise for children. This 15-year-old orphan is not connected to the Cleveland Street Scandal, but his parents died and he became homeless, living in the wood and taking odd jobs to earn food money. But to the police that was a grounds to send him to adult prison at hard labor for a year. That is not justice either.

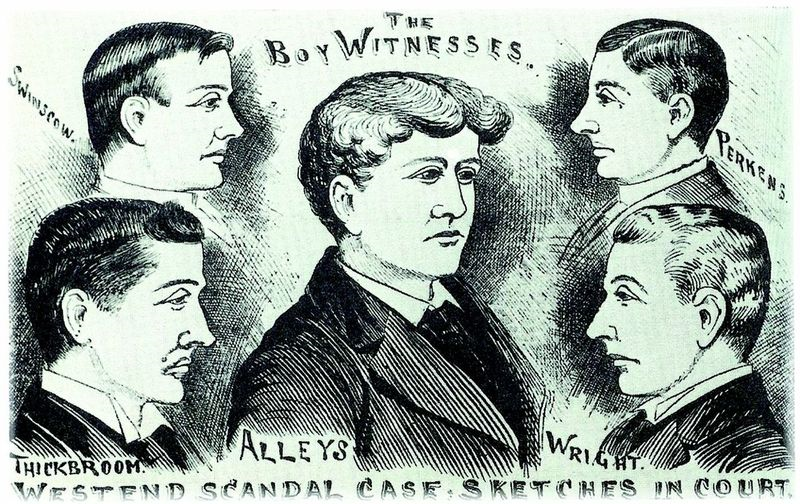

There was a series of thefts inside the General Post Office in Fitzrovia, which prompted London Police and Scotland Yard to investigate staff at the facility. They began with young boys who served as Telegraph Messengers. On 4th July 1889, 15-year-old Charles Swinscow was searched as part of this investigation.

It was a telegraph boys job to cycle around London delivering telegrams and urgent messages to homes and businesses. His wage would have been about eleven shillings per week, however when he was searched, eighteen shillings were found in his pockets, more than a weeks salary to such a young man. Swinscow was taken in for questioning as part of the police operation.

When asked how he came to have such a large sum of money in his possession, Swinscow panicked and confessed he'd been recruited by Charles Hammond to work at a house in Cleveland Street where, for the sum of four shillings a time, he would permit the brothel's clients to "have a go between my legs" and "put their persons into me".

He then identified a number of other young telegraph boys who were also renting themselves out in this manner at the Cleveland Street establishment, leading to the apprehension and questioning of Henry Newlove, Algernon Allies and Charles Thickbroom.

General Post Office before it was torn down, this scandal began in the basement of this building when Henry Newlove introduced Charles Swinscow to sex.

On July 15, 1889, a fifteen year old telegraph boy named Charles Swinscow was interviewed by Police Constable Luke Hanks in connection with a series of petty thefts at the Central Telegraph Office. Swinscow was found to have eighteen shillings on his person at the time of the interview, three to four times his weekly wage. PC Hanks asked Swinscow where he got the money. I got it doing some private work away from the office, Swinscow replied, adding that the work was for a gentleman named Hammond who lived at number 19 Cleveland Street and ordinary nondescript street situated between Regent Park and Oxford Street. PC Hanks repeatedly asked Swinscow what he had done to earn such a sum. I will tell you the truth, Swinscow eventually replied, I got the money for going to bed with gentlemen at his house.

It transpired that Charles Swinscow had been introduced to Hammond and the male brothel at 19 Cleveland Street by a fellow employee of the General Post Office, Henry Newlove.

In his statement, Swinscow told how, the previous September, I made the acquiantance of a boy named Newlove who was then a messenger in the Secretary's Office and is now a 3rd Class Clerk:

Soon after I got to know him he asked me to to into the lavatory at the basement of the Post Office Building- we went into one water closet and shut the door and we behaved indecently together, the boys masturbated each other- we did this on several other occasions afterwards. In about a week's time Newlove said as near as I can recollect "Will you come to a house where you'll go to bed with gentlemen, you'll get four shillings each time."

Swinscow claimed that he was reluctant to go to Cleveland Street but was at last persuaded by Newlove and the promise of money. Accompanied by Newlove, Swinscow went to Cleveland Street and was introduced to Mr. Hammond. he said--good evening, I'm very glad you've come, Swinscow recalled in his statement and detailed his first encounter with one of the Cleveland Street Brothel's Customers.

I waited a little while and another gentleman came in. Mr. Hammond introduced me, saying that this was the gentleman I was to go with that evening. I was to go into the back parlour, there was a bed there. We both undressed and being quite naked got into bed. He put his penis between my legs and an emission took place. I was with him about a half hour and then we got up.

Swinscow was not the only telegraph boy that Henry Newlove had recruited in this way for service in the Cleveland Street Brothel. George Wright was sixteen when he became friends with Newlove. Newlove used to speak to him in lobbies and eventually persuaded him to go down to the basement toilet. On one or two occasions, certainly more than once, Wright deposed, Newlove put his person into me, that is to say my behind and something came from him. Newlove took Wright to the Cleveland Street where he was introduced to Hammond. Another Gentleman came in who I should know again, Wright Said, a rather foreign looking chap.

I went with the latter into a bedroom on the same floor and we both undressed and we got into bed quite naked. He told me to suck him. I did so. he then had a go between my legs and that was all.

Newlove also persuaded George Wright to find another "nice little boy" to take to Cleveland street. Wright introduced him to a seventeen year old boy Charles Thickbroom.

Newlove took Thickbroom down to the basement lavatory of the old Post Office building and subsequently recounted to George Wright how he had tried to have anal sex with Thickbroom.

On one occasion at least Newlove told Wright I put my person into his hind parts. I could not get in, though I tried and emitted.

Almost by accident, PC Hanks had uncovered a network of male prostitution involving telegraphy boys. Scotland Yard was called in and a warrant for the arrest of Hammond was issued.

But when the police arrived at Cleveland Street to apprehend him that he had fled abroad. A warrant for Henry Newlove was also issued and he was successfully arrested and charged with the abominable crime of buggery against George Wright and divers other persons. Newlove was not prepared to carry the entire burden of the scandal, telling the man who arrested him, Chief Inspector Abberline of the Criminal Investigations Division of Scotland Yard, I think it is hard that I should get into trouble while men in high positions are allowed to walk free. What do you mean? Abberline asked. Why replied Newlove, Lord Arthur Somerset goes regularly to the house on Cleveland Street, so does Earl Euston and Colonel Jervois.

These were names to conjure with. Lord Arthur Somerset, nicknamed Podge was 38 years old and the son of the Duke of Beaufort and the Younger brother of Lord Henry Somerset, who had fled to Florence in 1879 to avoid a public scandal over his affair with a young man. Harry Smith.

British Post Office Messenger Thomas Swinscow before his arrest.

British Telegraph boys existed to well into 1950's London.

Dramatis Personae

Charles Thomas Swinscow 15 yrs Telegraph Boy - Arrested for 'theft'.

Henry Horace Newlove 16 yrs Telegraph Boy - GPO 'Recruiter' for Hammond

George Alma Wright 17 yrs Telegraph Boy - 'Performed' with Newlove for voyeurs

Charles Ernest Thickbroom 17 yrs Telegraph Boy

William Meech Perkins 16 yrs Telegraph Boy

Algernon Edward Allies 19 yrs Servant at the The Marlborough Club

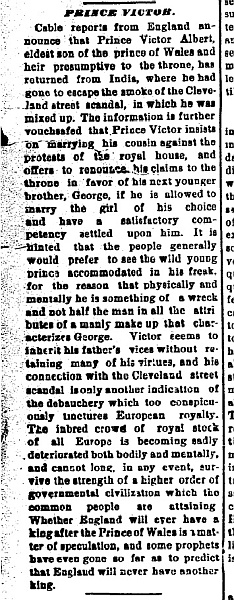

Prince Albert Victor (January 8th, 1864 - January 14, 1892), oldest son of Prince Edward, late King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra and Grandson of Queen Victoria.

Justice doesn't mean the same thing to everyone.

19 Cleveland Street was the site of one of the most serious scandals during the Victorian Era. Prince Albert Victor was implicated in the scandal by his friend Lord Arthur Somerset. Thinking is 50/50 that the Prince was involved, had knowledge or participated, but as a strategy it worked perfectly for Somerset, he was given advance notice of an arrest warrant and fled to France, probably the best place to live in exile. Several sources indicate that honest Inspector Abberline, famous for leading the Jack the Ripper Investigation, was appalled at how strings were pulled to protect the adults but the boys were sentenced to hard labor. Boys are beaten, tortured and raped in prison.

Chief Inspector Abberline at a Scotland Yard Staff Photo, the shy, efficient Inspector, avoided the spotlight even in this photo.

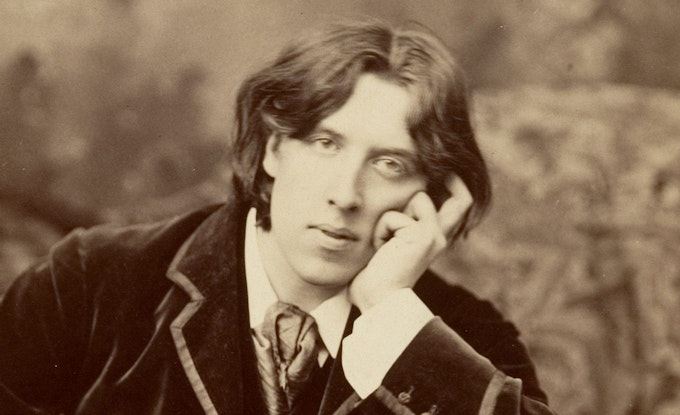

Lord Alfred "Bosie" Douglas the reason for Oscar's fall from Grace

In quick succession Jack the Ripper and The Cleveland Street Scandal led to a Puritan inspired Prosecution of all sex crimes. In 1894, Oscar Wilde would be ensnared in this Puritan pogrom

http://notchesblog.com/2014/12/02/uncovering-cleveland-street-sexuality-surveillance-and-late-victorian-scandal/

http://clevelandstreetscandal.com/

The characters making up the Cleveland Street Scandal

The Telegraph Boys

Henry Horace Newlove

16 yrs Telegraph Boy - GPO 'Recruiter' for Hammond

Charles Thomas Swinscow

15 yrs Telegraph Boy - First boy arrested for 'theft'

George Alma Wright

17 yrs Telegraph Boy - 'Performed' with Newlove for voyeurs

Charles Ernest Thickbroom

17 yrs Telegraph Boy

William Meech Perkins

16 yrs Telegraph Boy - ID's Lord Alfred Somerset as a 'client'

Algernon Edward Allies

19 yrs Houseboy - The Marlborough Club, used by Lord Somerset

George Barber

17 yrs George Veck's 'Private Secretary' and boyfriend

John/Jack Saul

30 yrs Infamous London rent boy - Possibly aka the Jack Saul

The Pimps

Charles Hammond

35 yrs Brothel keeper of 19 Cleveland Street, London

Rev. George Daniel Veck aka Rev George Barber

40 yrs Ex General Post Office (GPO) employee, lives at 19 Cleveland Street, sacked for indecency. coffee house in Gravesend, Kent. 18 year old 'son' who travels with him.

Police Officials

PC Luke Hanks Police officer attached to the General Post Office

Mr Phillips Senior postal official who questions Swinscow with Hanks

Mr C H Raikes The Postmaster General 1874-1880

Mr James Monro Metropolitan Police Commissioner

Frederick Abberline

46 yrs Police Chief Inspector, infamous for the 'Jack the Ripper' investigations in 1888, London's Whitechapel district

PC Richard Sladden

Police officer who carried out surveillance of the Cleveland Street brothel following Swinscow's arrest

Arthur Newton

Lord Arthur Somerset's solicitor. Later to defend Oscar Wilde at his trial in 1895 and notorious murderer Dr Crippen

Cleveland Street Clients

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence

25 yrs Rumored to be a 'Brothel Client' - Went on a seven month tour of British India in Sept 1889 to avoid the press & trials

Colonel Jervois of the 2nd Life Guards 'Brothel Client' - Winchester Army Barracks

Lord Arthur Somerset aka Mr Brown

37 yrs 'Brothel Client' - Named in Allies letters as 'Mr Brown'

Henry James Fitzroy

39 yrs Accused of being a 'Brothel Client' - Earl of Euston

Prosecutors

Sir Augustus Stephenson

Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP)

Honorable Hamilton Cuffe

Assistant DPP - Six years later he would prosecute Oscar Wilde at his trial in 1895 as the Director of Public Prosecutions

Journalist

Ernest Parke

Journalist - North London Press

The Cleveland Street Scandal by H. Montgomery Hyde Coward, McCann & Geoghegan; 1st edition (January 1, 1976)

The Cleveland Street Scandal

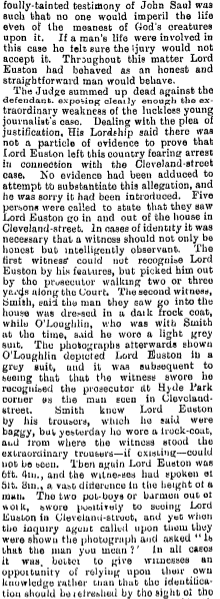

In late 1889 a police investigation discovered a male brothel on Cleveland Street, near Tottenham Court Road, which supplied boys from the Post Office to have sex with aristocratic gentlemen. One of the boys and a man who lived at the house pleaded guilty in return for a relatively light sentence, thus preventing the necessity of presenting evidence at a court trial. The authorities wished to hush up the affair because a large number of important men were implicated, including Lord Arthur Somerset, the Earl of Euston, and even Prince Albert Victor (second in line to the throne). The authorities successfully delayed the investigation until many men could flee the country, including the keeper of the house, and Lord Arthur Somerset. Rumours nevertheless circulated and early reports appeared in the American newspapers, and eventually a newspaper editor published some explicit charges in London. The Earl of Euston successfully sued the editor for libel, claiming that he had visited Cleveland Street only under the mistaken impression that he would see female striptease shows there, and in any case he certainly had not fled to Peru as the newspaper falsely alleged. Several telegraph boys testified that Euston was in fact a frequent visitor to Cleveland Street, and the notorious male prostitute Jack Saul testified that he had often had relations with Euston on the premises. This evidence was dismissed as "tainted" (how could it be otherwise?) and the editor was sent to prison for 12 months, though he was released after six months due to public outrage at the severity of the sentence. Somerset's lawyer was subsequently tried and imprisoned for perverting the course of justice by offering to maintain the telegraph boys if they emigrated. The keeper of the house attempted to blackmail his aristocratic clients from his new base in Seattle. The fiery Radical MP Henry Labouchere used his privilege in the House of Commons to expose the Prime Minister's involvement in the government conspiracy to prevent investigation and to allow important men to escape justice. The following account documents the scandal entirely through contemporary newspaper accounts, selected and slightly abridged to avoid repetition.

12 November 1889

A DISGRACEFUL LONDON CLUB SCANDAL.

Six sittings have been held at the Marlborough-street court, London, to inquire into abominable charges made against members of the West End club. Several lads, postal messengers, were arrested in connection with the case. The scandal involves an eminent liberal politician, an officer attached to the royal household and several peers. Some of the accused are reported to have fled. The magistrates who conducted the investigation sent a report of the result to the government, asking what course the authorities ought to follow. The government did not desire to spread the scandal if the offenders would exile themselves, and the proceedings have accordingly been abandoned. (Evening Star, Washington DC)

12 November 1889

A SCANDAL IN HIGH LIFE.

Several of the most distinguished families of England are under a cloud of scandal so hideous as to preclude the publication of the circumstances. So far as they may be touched upon they are that the police raided a house in Fitzroy square that has been frequented by high officials in the army, noblemen and others of elevated social standing. Their discoveries were such that active criminal prosecution of the offenders was begun and suddenly stopped. The reason was that the names involved were of the most influential men in the kingdom. The result is that there has been an exodus from England of several noblemen and gentlemen who have previously stood highest in English society. Lord Arthur Somerset, who resigned his commission in the guards last week in consequence of this scandal, has also resigned his position as equerry in the Prince of Wales' household. [Prince] Albert Victor's sudden trip to India is said to be not unconnected with discoveries made by police in Fitzroy square. The Earl of Euston and Lord Beaumont have also gone abroad, probably for their country's good. It is rumored that Chief Commissiner of Police Munroe has threatened to resign in consequence of the interference by the higher powers in thie prosecution of the men implicated in this scandal. (Wellsville Daily Reporter, New York)

13 November 1889

A great European sensation, and scandal that will cause many nabobs to leave the country, comes from London, in a dispatch dated the 9th, which reads as follows:

A horrible scandal in the private West End club has been exposed. Hundreds of members are implicated. Thirty warrants of arrest have been issued, but their execution is withheld on condition that the persons charged with crime leave the country. The offenders include future dukes, a duke's son, another peer, a Jewish financier, many honorables, a parson and several officers of the army. The latter suddenly resigned their commissions. All the principal offenders have fled. Efforts had been made to suppress the affair, but the story became known in the clubs and newspaper offices and the outline as above, which is all that can be given at present, is true in every respect. (Goshen Democrat, Indiana)

Prince Albert Victor, photograph by Bassano, c.1888

"Eddy", Prince Albert Victor, photograph by Bassano, c.1880

18 November 1889

The General Post Office torn down in 1900

WALES' HEIR INVOLVED.

THE LONDON SCANDAL CAN NOT BE HUSHED UP.

Albert Victor, Two Removes from the Throne, a Vile Wretch.

NEW YORK, November 17. – (Special.) – The following European news is clipped from the cables of this morning's papers:

LONDON, November 16. – During the time when John Bull is not swelling out his chest and returning loud thanks to the Creator who made him so much better than other people, it is his ill-luck to be engaged in discussing or trying to suppress the malodorous scandals which spring up eternally inside his island household. There is always something peculiarily offensive or attractive – whichever you liike – about a British scandal. It has become an axiom that when a bank cashier has been a particularly pious man his flight makes a bigger hole in the assets than ordinary. By the same rule, when anything happens in England to shock the proprieties so dear to the English bosom, these proprieties get an astonishing amount of sensation for their money.

Ten days ago it looked as if the official pressure was going to succeed in hushing up the

TREMENDOUS ARISTOCRATIC SCANDAL.

Everybody was talking about it, and passing on distorted versions to his fellows. But there was a general feeling that it would never get into the Courts. Now the prospect is different. Mr. Labouchere has said frankly in this week's Truth: "What if the matter is 'Burked' by the authorities, it will be brought up immediately when Parliament meets, and ventilated to the very dregs in the House of Commons."

This threat, ominously enough, follows a paragraph alluding to the costly apartments being fitted up for [Prince] Albert Victor in St. James' Palace, the expense of which the Commons will be asked to meet. No connection between these two paragraphs is suggested, but it is obvious to everybody that there has come to be within the past few days a general conviction that this long-necked, narrow-headed, young dullard was mixed up in the scandal, and out of this had sprung a half-whimsical, half-serious notion, which one hears propounded now about clubland, that matters will be so arranged that he will never return from India. The most popular idea is that he will be killed in a tiger hunt, but runaway horses or a fractious elephant might serve as well. What this really mirrors is a public awakening to the fact that this stupid, perverse boy has become a man, and has duly two highly precarious lives between him and the English throne, and is

AN UTTER BLACKGUARD AND RUFFIAN.

Heretofore people have not known much about him, save that he was a dull chap whose nickname was Prince Collars and Cuffs. The revelation now that he is something besides a harmless simpleton has created a very painful feeling everywhere. Although he looks so strikingly like his mother, it turns out that he gets only his face from the Danish race, and that morally and mentally he combines the worst attributes of those sons of George III. at whose mention history still holds her nose. It is not too early to predict that such a fellow will never be allowed to ascend the British throne; that is as clear as anything can well be. It is equally clear that the suppression of the scandal in which he, with some dozens of young and middle-aged samples of nobility and gentry of England is involved, has become impossible, and that every day the attempt is further persisted in will do enormous damage not only to the Government but to the aristocratic social structure generally. There is more indignation and ruffling of the equanimity of the English mind just now than I have ever seen before. Very little more repression will be needed to bring it to fever heat, but, as I have said, the whole scandal is going to come out.

The Paris press for a week has been full of the most exaggerated and sensational accounts of the thing. Le Matin leading the way in an outspoken onslaught on London society under the suggestive caption of

"LA SODOME MODERNE."

The effects of this terrible revelation, when sooner or later it is forced into daylight, can not but be prodigious upon the whole political and social edifice of contemporary England. From my points of view, the necessity of a full exposure will seem most lamentable, but there will be more than compensation if an effective blow is dwelt in this wretched little glass of titled young loafers and scoundrels who have brought the name of English gentlemen down into the mud. (Cincinnati Commercial Gazette)

20 November 1889

THE SCANDAL OF CLEVELAND STREET.

THREATENED PROSECUTION FOR LIBEL AND CONSEQUENT EXPOSURE.

The foul scandal which has filled London with prurient gossip since the end of September seems likely now to come into open court. The facts of the case are simple. In a house of evil fame in Cleveland-street, off Tottenham-court road, last September, the police seized two persons, a man of forty, named Veck, and a clerk of eighteen, named Newlove, who were accused of offences similar to those which led to the Cornwall-French trials in Dublin. Both at the police-court and at the Old Bailey the proceedings were smuggled through in secrecy, and all that is known in public is that Veck was sentenced to four months' [actually, 9 months] and Newlove to nine months' [actually, 4 months] imprisonment.

It was put about, however, on what seemed to be good authority, that a number of letters and cards were found by the police, which they seized, and used in compiling a list of frequenters of the house, the black catalogue containing the names of many persons of good birth, though of indifferent morals. Instead of acting at once on this information the Home Office refused to allow anything to be done until the matter was considered by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister shrank from all responsibility until he consulted his Cabinet.

Meantime, the chief persons accused had disappeared, and malicious gossip declares that the scruples of Ministers were carefully conceived in order to give time to the accused to depart, so as to avoid the exposure, which was dreaded.

At the first meeting of the Cabinet held after the recess warrants were issued against some of the accused, but all efforts to ascertain the names of those persons against whom the warrants were issued have hitherto failed.

Inquiries of the police (who, it might be thought, should be able to give information) elicit reports more or less misleading, and one of those reports finding its way into print has led to proceedings which will finally frustrate all the efforts that have been made to hush the matter up.

On Saturday next at eleven o'clock Mr. George Lewis, instructed by the Earl of Euston, eldest son of the Duke of Grafton, and heir to the title and estates, will apply for a fiat to take criminal proceedings against Mr. Parke, editor of the North London Press, for having stated that the Earl of Euston was mixed up in the Cleveland-street scandal, and that he had been allowed to leave the country and to defeat the ends of justice.

There is therefore every probability of the whole noisome matter, with the names of those concerned, being brought into the public courts, and everything turns upon the question of identity. If tried as a case of mistaken identity, then the witnesses called for the defence of Mr. Parke will be liable to examination and cross-examination concernng every person whom they can swear they met at the house in question.

The prospect is anything but pleasant either for the public or for the parties concerned, but the course taken by Lord Euston seems to render it inevitable.

Mr. Labouchere in Truith of to-day says: – A nobleman [i.e. Lord Arthur Somerset] holding a position at Court was implicated by the depositions of the Postal inquiry that had taken place, and by the telegraph boys who would have been called as witnesses if the prisoners had not pleaded guilty. He was asked by a high Court official to explain matters, and at once fled the country. Hamond, the owner of the house, has also gone abroad. Warrants were subsequently issued against these two men. I am further informed that the house was not let to Hamond, but to four gentlemen. The names are known, and are common talk at every club. It is pretty clear that matters cannot be allowed to rest here. Very possibly many who are suspected are innocent, and in their interest, as well as in the public interest, no effort should be spared to bring home the guilt to those really guilty. (Pall Mall Gazette)

[At the trial at the Old Bailey, George Daniel Veck, age 40, and Henry Horace Newlove, age 18, together with Charles Hammond, not in custody, were charged "for procuring George Alma Wright and others to commit certain obscene acts, and also to conspiracy". Veck pleaded guilty to the 16th and 17th counts and was sentenced to nine months' imprisonment with hard labour, while Newlove pleaded guilty to the first thirteen counts and was sentenced to four months' hard labour. According to the more detailed Trial Calendar of Prisoners (TNA CRIM19, piece 35), Veck, a minster, was taken into custody on 20 August 1889, and tried on 18 September, on the charges of "Conspiring and agreeing together with Charles Hammond to incite and procure George Barber, George Alma Wright, Charles Thomas Swinscow, Charles Ernest Thickbroom, William Meech Perkins, and Algernon Edward Allies, to commit an abominable crime", as well as committing an act of gross indecency with George Barber and Algernon Edward Allies. He pleaded Guilty to Gross Indecency and was sentenced to nine months in Pentonville Prison. Newlove, a clerk, was taken into custody on 8 July, and tried on 18 September, on the charges of procuring the commission by the aforementioned youths Barber, Wright, Swinscow, Thickbroom, Perkins, and Allies "of divers acts of gross indecency with other male persons", and further charged with himself "attempting to commit an abominable crime" with Wright, and actually "committing acts of gross indecency" with Wright and with Swinscow. He pleaded guilty to procuring the commission of gross indecency by male persons and was sentenced to four months in Pentonville Prison.]

21 November 1889

THE LONDON SCANDALS.

It is generally agreed that the early weeks of the session will be taken up first with the debate on the Address, and next with even more prolonged discussion n the genesis of the Parnell Commission. It is, however, quite on the cards that another subject may thrust itself to the front, with a result deeply hurtful, if not fatal, to the Government. This is what is now known as the Cleveland-street scandal. Mr. Labouchere has taken this matter in hand, and knows a great deal more about it than he discloses in the pages of "Truth." He will, he expects, be able to bring home to the Government a grave charge of collusion, directly and indirectly, with the titled criminals who have fled, leaving in the lurch some inconsiderable men and boys whose case was secretly disposed of in one of the police courts. For political reasons a majority in the House of Commons may cling to the Ministry through thick and thin where the question is merely one of Home Rule for Ireland. But it is very different when it comes to a case of hoodwinking justice and assisting the escape of abominable criminals because they happened to be of aristocratic birth and well known in society. The English people are swift to anger in a matter of this kind; and any member, whatever his politics, who assisted in shiedling a Minsitry against whom even grave suspicion on such matters rested would have little chance of re-election. (Northampton Chronicle and Echo)

21 November 1889

The Prince of Wales arrived in London, on his return from Athens, at one o'clock on Monday morning, and he did not sleep late, for before the luncheon-hour on that day it became known among his entourage that he had determined to have what is now frankly called "the scandal of Cleveland Street" completely investigated, and, if found necessary, publicly exposed. It was in consequence of this resolution that, after having received that afternoon at Marlborough House a visit from the Duke of Cambridge, the Prince subsequently the same day went to Gloucester House to have another interview with the Commander-in-Chief, for well-known men both at the Court and in the army are alleged to be involved. What would have followed from this prompt action on the part of the Prince of Wales can hardly now be guessed, for the announcement made to-day that criminal proceedings for libel against a suburban newspaper will be taken for having directly charged the son of a peer with being concerned in the scandalous affair, will precipitate a legal enquiry, which cannot end until all the truth be learned. From various points of view the necessity for such an investigation is deplorable, but matters had gone so far that it was impossible much longer to hush up the affair. (Birmingham Daily Post)

23 November 1889

WARRANT ISSUED.

Following the application in Chambers to Mr. Justice Field, upon which the learned judge authorised criminal proceedings against Ernest Parke, editor of the North London Press for libelling the Earl of Euston, Mr. Goerge Lewis this afternoon at Bow street made a formal application to Mr. Vaughan for a summons against Mr. Parke. Mr. lewis entered the court at half-past three, accompanied by Lord Euston, but the application was not immediately made, his Worship being occupied in hearing a case. The sworn information of Lord Euston set forth that the North London Press on the 16th November published a paragraph stating that on September 28 that journal said that amongst a number of aristocrats mixed up in the indescribable, loathsome scandal in Cleveland street, Tottenham Court road, was the heir of a Duke, the Earl of Euston, who had departed to Paris. The paragraph also alluded to the younger son of a Duke, and said, "These men have been allowed to leave the country because their prosecution would disclose the fact that a few more distinguished and more highly placed personages than themselves were inculpated in this disgusting crime. The crminals in the case are to be numbered by the score." These allegations affecting himself Lord Euston declared untrue and also informed the Court that Ernest Parke, of the Star newspaper and North London Press, was the person against whom he applied for a warrant. At four o'clock Mr. Lewis made a formal application to his worship, first reading Lord Euston's deposition. Lord Euston was then sworn, and deposed to the truth of his affidavit. Mr. Vaughan thereupon ordered a warrant to be issued. (Sheffield Evening Telegraph)

23 November 1889

. . . As only one name is involved in this particular suit, it may be that even a plea of justification on the part of the defendant newspaper would not avail to have the whole case thoroughly investigated; but it is scarcely possible for the enquiry to end without bringing in the names of various well-known personages. One of these is now openly given in print, and no proceedings on his behalf have yet been instituted, it being understood that he is not in England.

From the public point of view the gravest feature of the charges now made is not that affecting individuals, but highly-placed members of the Cabinet. The accusation is briefly this: That the information affecting the keeper of a certain house in Cleveland Street and some of its alleged frequenters, including a Court official, was in the hands of the authorities at the end of July; that for two months this, as far as these persons were concerned, was not acted upon; that immediately after the newspaper now involved had pointed to the existence of the scandal the keeper of the house and the Court official, against both of whom warrants are asserted to have been subsequently issued, fled the country; that the resigation by the latter of his various posts was received and gazetted some weeks later; and that in the meanwhile, at the suggestion of our own Foreign Office, the keeper of the house had been expelled from France as a mauvais sujet. This last point is a charge of peculiar gravity, and abundant evidence of its truth must be awaited before it can in any way be credited. How necessary is reserve at this juncture will be shown during the progress of the coming enquiry, in which, I hear, Mr. Lockwood, Q.C., will lead for the defence. (Birmingham Daily Post)

25 November 1889

OUR LONDON CORRESPONDENCE

For some weeks past paragraphs have appeared in many journals hinting at a great scandal in the West End of London, implicating several well-known noblemen. These innuendoes also set forth that two of the delinquents in poor circumstances, were convicted of the offence at the Central Criminal Court, but that the trial was taken at an unusual hour in the morning in order that it might be hurried through without the knowledge of the public. If the other statements are as baseless as the last mentioned all I can say is that the scandalmongers have found a mare's nest. The trial referred to took place last September in the open court, and was duly recorded in the Old Bailey Sessions papers. The two men pleaded guilty, and not a word was said by counsel to eonnect them with the West End scandal, save that the house where the crime was committed was situated in Cleveland Street, Cavendish Square. One was sentenced to eighteen months' imprisonment and his companion to nine months. The proprietor of the house, said to be an unbeneficed clergyman, was indicted along with them, but he absconded before the trial and has not been heard of. A local newspaper called the "North London Press," which has been in existence for only a few months, gave what it called an authentic account of the scandal, stating that one of the noblemen implicated was Lord Euston, and that his lordship had run away to Peru. The editor of this journal is named Ernest Parke, and is also sub-editor of Mr T. P. O'Connor's "Star." Lord Euston has commenced an action for libel against him, and on Saturday afternoon obtained a warrant for his arrest from the magistrate at Bow Street. Mr Parke has surrendered himself to this warrant, and is at the moment of writing in the cells of the Bow Street Police Station, the officer in charge having declined to grant bail. Mr Parke will be brought before the magistrate this morning.

Lord Euston, who has brought the charge against the editor, is the eldest son of the Duke of Grafton, and consequently heir to the dukedom. He is a tall, slender man, between thirty-five and forty years of age, with a long blonde moustache. In his time he has seen a good deal of life. Four or five years ago he tried to get his early marriage nullified, but the skilful strategy of his solicitor, Mr George Lewis, and the able advocacy of Sir Charles Russell were of no avail, and his lordship's suit was unsuccessful. The Countess of Euston, and prospective Duchess of Grafton, lives in one of the terraces around Regent's Park, on a liberal allowance provided out of her husband's estates. Since then, Lord Duston himself has seldom been heard of, except in Freemasonry. Of late years he has taken much interest in ths pursuit, and is at this moment Provincial Grand Master of one of the Midland counties. The best proof that he has not gone to Peru, as stated in the "North London Press," was his appearance at Bow Street on Saturday afternoon in company with his solicitor, Mr George Lewis, to swear the information against Mr Ernest Parke. The development of the case will be interesting. As an authentic statement will be made to-day it is useless even to hint at the many rumours flying about the clubs – many of the most sensational and exaggerated kind – as to what the forthcoming evidence will be. (Bradford Daily Telegraph)

26 November 1889

THE ALLEGED WEST-END SCANDALS.

DUKE'S SON VERSUS EDITOR.

PROSECUTION FOR LIBEL.

WILL THE SCANDALS BE EXPOSED?

SPECIAL DETAILED REPORT.

LONDON, Tuesday. – At Bow-street Police Court this afternoon, before Mr Vaughan, Mr Ernes Parke, the editor of the North London Press, was charged on remand with having published in an issue of the paper on the 16th November a libel of a nature already reported regarding the Earl of Euston, of 4, Grosvenor-place, London, and Eaton Hall, Thetford, the son of the Duke of Grafton.. The alleged libel was contained in a paragraph headed "The West-end Scandals." – Mr George Lewis prosecuted. – Mr Lockwood, Q.C., M.P., and Mr Asquith, M.P., were counsel for the defendant, and watching briefs were held by Mr Gill, barrister, and Messrs B. Abrahams and A. Newton on behalf of other persons whose names had been mentioned in connection with the scandals.

The proceedings commenced shortly after 3 o'clock, at which time the Court was crowded.

Mr Lewis in opening the case said Lord Euston complained of a libel pubilshed by the defendant in a paper called the North London Press, of Nov. 16th, 1889. The newspaper was not registered at Somerset House, as required by law, but he should prove that the defendant was the proprietor and editor. The libel charged Lord Euston with having committed a felony. The libel had already been before the bench, and the magistrate would notice it was alleged that the Earl of Euston was "one of a number of distinguished aristocrats who were mixed up in the indescribably loathsome scandal in Cleveland-street, Tottenham-court road," and it went on to say that these men had been allowed to leave the country. Now, if there had been the least inquiry, it would have been ascertained that Lord Euston was living where he always lived at 4, Euston-place. It went on to say that these men had been allowed to leave the country "because their prosecution would disclose the fact that a few more highly-placed personages than themselves were inculpated in this disgusting crime." The libel, therefore, was that Lord Euston had committed a felony of an atrocious character, and that was the libel for which he should ask the Court to commit the defendant to take his trial. The circumstances, so far as Lord Euston was concerned were these: He would say that he had never committed any crime of any sort or kind, and that this statement was absolutely without foundation so far as he was concerned; that he never left the country, and that there had never been any warrant out for his apprehension. The whole thing, in fact, was a fabrication from beginning to end. All Lord Euston knew of the matter was simply this:– That one evening, at the end of May or the beginning of June, he was walking in Picadilly at eleven o'clock, and a man put a card into his hand, on which were the words "Pose Plastique;" then the name of the proprietor, and "Cleveland-street, Tottenham Court-road." Lord Euston did not know what became of the card, but about a week afterwards he went at 11 o'clock at night. A man opened the door and asked him for a sovereign, which he gave him, and he was shown into the parlour. Then the man made some indecent proposal to him, and he called him a filthy blackguard and said he would knock him down if he did not allow him to pass, and then he went out of the house. That was all the knowledge which he had upon this matter.

Evidence was first given that Mr Parke was the proprietor and editor of the paper.

Lord Euston was then examined by Mr Lewis. He had seen the North London Press of November 16th, and he at once gave instructions for criminal prosecution for libel in respect of matters contained in that paper.

Is there any truth, Lord Euston, that you have been guilty of the crime alleged in the paper against you? – Certainly not.

Continuing, witness said there was no truth in the statement that a warrant had been issued for his apprehension. He had not been out of England since he came back.

Will you state in Court what you know of this house in Cleveland-street? – All I know is that I was waking one night in Piccadilly, I can't say the date, but it was at the end of May or the beginning of May [he meant June], when a card was put into my hand which was headed "Pose Plastique, Hammond, 19, Cleveland-street." Witness, continuing, said he went there about a week afterwards, about half-past ten o'clock at night. The door was opened by a man who demanded a sovereign, which he gave him. He then asked when the poses palstiques were going to take place. The man said there was nothing of that sort.

Mr Lockwood here objected to the conversation being repeated.

Mr Lewis: The libel alleged that Lord Euston was mixed up in having committed crime in Cleveland-street. He had a right to show what he did.

Mr Lockwood: I have no objection to Mr Lewis showing what Lord Euston did, but what he said his learned friend was not entitled to refer to.

Mr Vaughan agreed with Mr Lockwood.

Examination continued: Witness said he left the house immediately, and he had never been there since or previously. He had no knowledge of the house other than the one visit in connection with that house. If not objected to, you came here prepared to state what had passed? – I did. This concluded the examination.

Mr Lockwood said he did not propose to enter into any detailed cross-examination, because his client wished the matter to come before the final tribunal as soon as possible. He would, however, ask a few question.

Cross-examined by Mr Lockwood, the witness said he had been in the army, in the Rifle Brigade; but he was gazetted out, in 1871, he thought. He was now in the 1st Volunteer Battalion Northamptonshire Regiment. The newspaper in question was first brought to his attention on Monday of last week. He at once gave instructions for a prosecution.

Now this statement that you have made to-day – When did you first make it? – About the middle of October.

This thing happened, as I understand, in the month of June, and your first statement with regard to it was made in the month of October? Have you made a statement to the Home Office about it? – No.

At the Treasury? – No.

Have you made no statement to any official either at the Treasury or the Home Office? –I have had no communication of any sort or kind with any official either at the Treasury or the Home Office. That I swear.

You said that the first statement you made was in October – to private friends, I presume? – Yes, to private friends.

Is Lord Arthur Somerset a friend of yours? – I know him.

Where did you see him last? – Last summer; sometime during the season. I have met him in society. I have not seen him since.

Do you know where he is? – I do not know where he is.

After this occurrence in May or June you say you read the card? – Yes.

How long afterwards? – When I got home. I think when I got home and took my coat off. I could not read it in the street, and shoved it into my pocket; and when I got home I took it out to see what it was.

Was it a printed card? – It was lithographed, but "pose plastique" was in writing.

Was the gentleman who was giving out these cards in Piccadilly distributing them generally or were you specially favoured? – I cannot tell. I was walking along, and one was shoved into my hand. I cannot tell whether he was distrubting them promiscuously. I did not see him give a card to anybody else.

You had not time to stop and read it under the lamppost? – No. I do now know what you are laughing at. I did not think of stopping to read it under the lamppost.

How long elapsed between your looking at the card and going to the house? – At least a week.

Then of course you kept the card during that time? – Yes, I did. I should say I went to the house about the second week in June between half-past ten and eleven o'clock.

What became of the card? – I destroyed it. I was so sigusted at what I found at the place that I did not want to have anything more to do with it.

Did you burn it or tear it up? – I should think I tore it up.

You remember tearing it up in disgust and indignation? – Yes; I was very angry with myself for having been there.

From what passed in that house you have no doubt in your own mind what the character of the house is that you went to? – Not the smallest.

It is a house, as I understand you to say, of your own knowledge – where crimes such as those alluded to in the libel was probably being committed? – I should think that they might have been committed there, and probably were from what was said to me.

That was your experience of the house? – Yes.

Re-examined by Mr Lewis: You have been asked from what passed in the house if you have any doubt as to the character of the house. what did pass and what did the man say to you after you had given him the sovereign, and after the inquiry as to the "Pose plastique?" – He said, "There is nothing of that sort here."

Witness here described how a disgusting proposal was made to him.

What did you say? – I said, "You infernal scoundrel, if you don't let me out of the house at once I will knock you down."

And did you at once leave the house? – I did. Up to the moment that he made that statement to you, had you any knowledge whatever about this house other than what appeared on the card? – None whatever.

The Magistrate: Nor any suspicion? – Lord Euston: No.

Mr Lockwood (to the magistrate): That Sir, at present, is all I have to ask Lord Euston.

Mr Lewis: You had never been there before? – No.

Nor heard of it until recoveing that card? – No.

You were asked whether your first statement about it was not made until October. Was it until October that some public mention was made of this case? – Thereabouts.

From what you heard?

Mr Lockwood objected to the witness being asked what he had heard.

The Magistrate: How came you to make the statement in October?

Lord Euston: Because a rumour had got about, and I went and consulted with some friends of mine as to what I should do.

Mr Lewis: Then you made the statement to several friends? – Yes.

In reply to the questin as to whether he had anything to say, Mr Parke said. "I reserve my defence."

Mr Vaughan then commimtted him for trial at the next sessions of the Central Criminal Court.

Mr Lockwood said he hoped that in considering the qustion of bail, his Worship would bear in mind the fact that from the first Mr Parke had shown anxiety to meet the charge, and had not shown the slightest intention of shrinking from it. Mr Vaughan said it was a case of very great gravity, and he should require such bail as would certainly secure the attendance of the defendant at the trial which would take place next month. "I shall require two sureties in £250 each."

These were forthcoming, and Mr Parke left the court with his friends. (Hull Daily Mail)

27 November 1889

THE WEST-END SCANDALS.

This week's issue of Truth states, with reference to the Cleveland Street scandal, that in [the] middle of September George Daniel Veck, forty, and Henry Horace Newlove, eighteen, were arraigned at the Old Bailey, pleaded guilty, and were sentenced, one to nine months' imprisonment and the other to four months. Information respecting the house in Cleveland Street was first given by a lad employed in the General Post Office in June. Hammond fled the country. Newlove was arrested on July 8th and Veck on August 20th. Newlove admitted everything. A nobleman [i.e. Lord Arthur Somerset] connected with the Court fled upon explanations of his conduct being required. He was afterwards gazetted out of the army. (Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette)

1 December 1889

TO OUR CORRUPT ARISTOCRACY.

PATRICIANS, – History teaches us that moral corruption has always been the forerunner of your downfall. It was so in Greece, Rome, the Italian Republics, and France before the Revolution. There is no example to the contrary; so we may take it that this shocking depravity of the English aristocracy at this moment is the symptom of their approaching dissolution. Your friends in the State may try to hide your shame; a class Government may interpose with the police on your behalf; magistrates and judges may assist in the conspiracy; but vice, like murder, will out. All the world is aware that many among you have been guilty of unspeakable crimes, from the consequences of which you aRe shielded by your position, influence, and wealth. Two of the minor instruments of your unbridled lust have been punished; but you, the authors and instigators, walk freely abroad, although your names and the details of yourr crimes are known to the public and the police.. Here is a lesson for the democracy to take to heart. The aristocracy, our governors, may with impunity commit crimes for which humbler citizens are punished with severity. Hence it is clear that the laws are made by the classes for the oppression of the masses.

. . . Where, I ask, are the thousand and one moral organizations of the country, when criminal vice in high places is being protected by the authorities? Is a common jade, or something worse, to direct the counsels of the Cabinet? Are hermaphrodites enthroned in Scotland-yard? Is the ensign of the great united Tory and Coercionist party in future to be a he-goat, or a lump of mud? Shall Cabinet meetings be movable feasts – now sitting in Cleveland-street, now in Pimlico? Where are the depositions of the boys of the one place and of the rosebuds of the others? Must our mouths remain closed while this foul crime is being perpetrated in the sight of man? Or must we expect that in the coming time there will be attached to the bureau of every Tory Minister, as there is attached to the person of the shaw of Persia, a boy-favourite, and that the meetings of the Primrose League Dames will be presided over by a battered trull? . . . (Reynolds's Newspaper)

1 December 1889

. . . Many years back something of the same sort took place, and possibly the police may point to it as a precedent for what they have now done. The Bishop of Clogher was arrested in the act of perpetrating what was then a capital crime, with a private soldier of the Guards. They were both arrested, but on learning the high position of the right reverend culprit, he was admitted to bail, and forthwith absconded abroad, and was no more heard of. What became of his accomplice we know not. The existence amongst us of a Sodomite institution is a matter of a far more serious nature than his lordship, judging by the way in which he gave his evidence, would seem to think. The most severe measures the law will admit of should be resorted to in order to stamp out practices of an unnatural and revolting shape too hideous even to be mention[ed].

Indeed, the general conduct of the police in protecting highly-placed delinquents, and hunting down minor culprits has at last awakened public indignation, and many who had hitherto been blinded by the silly old saying that all persons were equal in the eyes of the law have come to the conclusion that the very reverse is the fact. . . . (Reynolds's Newspaper)

Illustration from Police Gazette

7 December 1889

THE WEST END SCANDAL.

IMPORTANT STATEMENT.

A London correspondent telegraphs that the wife of the man who kept the house in Cleveland-street is understood to be in communication with the police. It is stated on good authority that she has supplied the authorities with the names of a large number of persons who frequented the place, and some of them are individuals highly connected. The police are vigorously at work upon the case. (South Wales Echo)

14 December 1889

Illustration of the Earl of EustonThe Earl of Euston, who is the prosecutor in the case which, it is believed, will be means of bringing to light the Cleveland street scandal was forty-one on Thursday week. He married when he was two-and-twenty Miss Kate Walsh, and has no children. His father, the Duke of Grafton, Earl of Arlington and Euston, Viscount Thetford and Ipswich, Baron Arlikngton of Harlington, Middlesex, Baron Sudbury, Suffolk, is hereditary Ranger of Whittlebury Forest, and an Honorary Equerry to Her Majesty. The Duke was born in 1821, and is a widower. In addition to Lord Euston there are two sons, Lord Alfred Fitz-Roy and the Rev. Lord Charles, Rector of Euston and Honorary Chaplain to the Queen, and one daughter, the lady Eleanor Harbord. Lady Eleanor's first husband was Mr. Hubert Fitz-Roy Eaton, who died on the 8th of April, 1875. On the 5th of May, 1875, the widow married Mr. Harbord. (Shefrield Weekly Telegraph)

17 December 1889

THE LONDON SCANDAL – A NEW DEVELOPMENT.

The ghastly Cleveland Street scandal has been galvanised into life again by a variety of circumstances happening concurrently. In the first place, the opening of the December Session of the Central Criminal Court at the Old Bailey yesterday has directed public attention to the prosecution of Mr. Ernest Parke by Lord Euston for libel, the grand jury having found a true bill. the arrival of the American mail yesterday, bringing with it the American newspapers, has been eagerly expected, for it is well known that the representatives of Yankee journalism have been busily engaged in hunting up all the facts which could be ascertained, and telegraphing them without reserve to the newspapers by which they are employed. Indeed, one enterprising paper has had an ex-detective "on the job," and the result is a mass of "copy" in which names, which could not be mentioned here under penalty of actions of libel, are freely given, including one of very high standing indeed. The papers which have gone fully into the matter cannot be purchased in London, every copy having been bought up. Last night it was rumoured that the Treasury had taken action which will necessitate the complete disclosure of the whole business. If, as is supposed, a Government prosecution of the principal offenders is about to be instituted, an applciation will probably be made to-morrow to postone the trial of Mr Parke until the Treasury prosecution has taken place. (Glasgow Evening Post)

Illustration from Police News

18 December 1889

THE WEST END SCANDALS.

MR LABOUCHERE INDICATES THE STORY.

In the matter of the Cleveland Street scandals are such of the facts as can be recounted, and most of which were brought out in the evidence submitted to the Magistrate at Marlborough Street Police Court. A lad connected with the Post Office was suspected of stealing, and the matter was placed in the hands of the police. On July 2 he was called before Mr Phillips, an official of the Office, and was qustioned by a constable named Hanks. The lad explained that he had obtained the money of which he was in possession at 19 Cleveland Street. He incriminated other lads, who on being called told the same story. All stated that they had been induced to go to Cleveland Street by Newlove, a clerk in the Post Office; that the house in Cleveland Street belonged to one Hammond; and that a clergyman, or a person who dressed as a clergyman and called himself one, named Veck, was Hammond's confederate. On July 7 Newlove, who was being taken to the Police Court, gave certain names to Constable Hanks, and on July 8 he gave a name to Inspector Abberline. On July 9 Hanks went to Newlove's mother's home. When there Veck called, offered to get a solicitor to defend Newlove, and to give money. This was overheard by Hanks. On August 30 Veck was arrested, and he and Newlove were charged before the Magistrate at Marlborough Police Court. The case was heard on that day, on August 27, on September 3, and September 4. On this last day the two were committed. They were almost surreptitiously put in the dock of the Old Bailey, when there was hardly any one in the Court, pleaded guilty, and were sentenced to a few months' imprisonment by the Recorder. Hammond, the proprietor of the house, had fled the country on July 6. On July 5 Newlove had told Hammond that an investigation was taking place. On July 6 Hammond and Veck were seen to leave Cleveland Street – the former with a carpet bag. He was subsequently seen in Paris. Thence he went to Brussels, and then embarked for the United States, where he now is. On July 9 Constable Sladden was put to watch the house in Cleveland Street with another person (probably one of the lads). With this other person he watched until July 12. He saw "a great many gentlemen" come to the house, ring at the bell, and when it was not answered go away. On July 10 the furniture was removed, and on that day Veck passed three times before the house. From the 13th to July 30 he watched the house alone. The lads gave full descriptions of several of the gentlemen they had seen at the house. For instance, four them gave these details of evidently the same individual:– A very tall man, with little side whickers, a moustache short cut, and hair of a light colour; a very tall man, with light brown hair, and side whiskers of reddish hue, he wore his hat on one side; the man was in evening dress, had red whiskers, rather long, a moustache, a bald head, and was about 6 feet 2 inches or 3 inches; a rather tall man, with side whiskers, a bald head, and rather fair. A warrant, after considerable delay, was obtained against a nobleman [i.e. Lord Arthur Somerset] who was one of the visitors. But what then happened? His friends applied to Mr Monro to state whether he was compromised. Mr Monro naturally declined to reply. On October 18 Lord Salisbury was applied to. He at once said that the nobleman would be arrested the next day. On the evening of the day that this intimation was so benevolently given the person put himself out of British jurisdiction, and went to Vimille, near Boulogne. From there he went to Conxtantinople, via Brussels, and offered his services to the Sultan. He is now, I believe, in Hungary. At Constantinople (and this shows more than anything else the criminal wickedness of allowing him to escape) he explained that he had left England to screen a highly-placed person – a falsehood of the basest and most baneful description. But what are we to think of the almost nominal sentences on Veck when he pleaded guilty! I assert that a grosser miscarriage of "justice" never took place in a Court of law than this sentence. It is quite impossible that this can be passed over. (Dundee Evening Telegraph)

19 December 1889

THE LONDON SCANDALS.

An American correspondent telgraphs:– The man Hammond, the keeper of the Cleveland Street house, has been traced by the New York World to Seattle, in Washington Territory. He is living in that town with a woman who is said to be his wife and two boys, one of whom he says is his son. He told a World reporter that he knew all about the West End scandals in London, but denied that he had anything to do with them personally. (Dundee Evening Telegraph)

19 December 1889

TO-DAY'S TITTLE TATTLE.

A somewhat startling development of the Cleveland-street scandal is reported in this morning's papers. Lord Arthur Somerset's lawyer, Mr. Newton, together with one of his clerks and an interpreter, have been summoned for conspiring with other persons to obstruct, pervert, and defeat the course of law and justice. The accusation, I believe, is that Mr. Newton and his clerks employed themselves to assist Hammond, the keeper of the house in question, to migrate to the United States. The inference, of course, is obvious. Mr. Newton as an individual had no interest in removing Hammond beyond the jurisdiction. But some other person or persons had, and they seem to have had plenty of money at their disposal. Mr. Newton may, however, be able to clear everything up [when] he appears to answer to the summonds. (Pall Mall Gazette)

19 December 1889

THE CLEVELAND-STREET CASE.

THE PARKE TRIAL POSTPONED TILL JANUARY.

At the Old Bailey this morning Mr. Ernest Parke, editor of the North London Press, was formally indicted for publishing in that journal a libel on Lord Euston in connection with the Cleveland-street case. Mr. Parke pleaded not guilty.

Mr. Asquith (for the defence) put in a plea of justification, stating that the alleged libel was published without malice and was true in substance and in fact.

Mr. Lionel Hart, who said he appeared with Sir Charles Rusell and Mr. Mathews for the proseuction, applied that the case might stand over until the next sessions, so that his learned friends with himself might have a further opportunity of grappling with the case, which was so very peculiar.

Mr. Asquith said that he had not been able – according to the usual practice – to inform the other side of the plea until just beforehand, and that while Mr. Parke was vey anxious to meet this charge, he would order no objection to the postponement.

The Recorder said that the application was quite reasonable, and ordered that the case should stand over until the January sessions.

Mr. Parke then left the dock. (Pall Mall Gazette)

24 December 1889

THE CLEVELAND-STREET CASE.

A SOLICITOR SUMMONED.

At Bow-street Police-court yesterday Mr. Arthur Newton, solicitor, of Great Marlborough-street, Mr. F. Taylerson, articled clerk, and Mr. Adolphus de Galla, interpreter, were summoned before Mr. Vaughan for having, "on the 25th of September, and at divers times between that date and the 12th of December, unlawfully conspired, combined, confederated, and agreed together, and with divers other persons, to obstruct, prevent, and defeat the due course of law and justice in certain proceedings then pending at the Marlborough-street Police-court and at the Central Criminal Court, in respect of offences alleged to have been committed by divers persons at 19, Cleveland-street, Fitzroy-square, in the county of London, and to obstruct, divert, and defeat the due course of law and justice in respect to the said offences."

Mr. Horace Avery, instructed by Sir A. K. Stephenson, solicitor to the Treasury, conducted the prosecution; Mr. Gill, barrister, defended Mr. Newton, and Mr. St. John Wontner appeared for the other defendants.

Mr. Avory, in opening the proceedings, said that on July 4 last a telegraph messenger in the service of the Post Office was questioned by a constaable on the establishment as to some money that was missing, and accounted for money in his possession by stating that he obtained it at the house, No. 19, Cleveland-street. Other boys were also indicated as having visited the house, and statement were obtained from lads named Wright and Thickbroom. All of these boys mentioned a lad named Newlove, also in the service of the Post Office, as the person who had introduced them to the house. The lads were thereupon suspended and the matter placed in the hands of the police, with the result that warrants were obtained against Newlove and a man named Hammond, who was alleged to be a principal in the matter. Newlove was arrested on July 7, but as, on his suspension, he had communicated the fact to Hammond, that person contrived to escape, and the house was closed. Newlove was remanded from time to time, and on the 25th July the matter was placed by the Home Office in the hands of the Director of Public Prosecutions. Inquiries were then made and statements taken for the purpose of ascertaining how far, if at all, the evidence of these lads could be corroborated, as it was clear that no charge of visiting and using the house could be sustained against any person upon the mere statement of accomplices. On the 20th of August, Veck, a man who habitually assumed the garb of a clergyman and who could be indentified by independent witnesses as one who assisted in the management of the concern, was arrested. Documents were found upon him which directed the attention of the police to a boy named Alliss, who lived at Sudbury, in Suffolk. On the police going to that address on the 23d of August they found that, in consequence of an anonymous letter received on the previous day, the lad had destroyed a number of letters which might have afforded valuable corroborative evidence against visitors to the house. Next day Alliss was brought to the Treasury, and on the same day the defendant De Galla, it was believed, called on the parents at Sudbury and inquired whether their son had left any letters at home. He was answered in the negative, and told that the police had taken him away; on which he remarked that he wished he had called earlier. At the police-court Alliss and other boys gave evidence against Hammond, and also against other person, whom they could describe, but without knowing who they were. On the 11th of September Newlove and Veck were committed for trial for offences against the Criminal Law Amendment Act, and on the 18th they were brought up in the ordinary way at the Central Criminal Court, and having pleaded guilty to various counts in an indictment in which Hammond was included, they were sentenced to terms of iprisonment. Mr. Newton had throughout acted as solicitor for the defence, and on the 24th of September Taylerson, his clerk, visited Alliss's parents, and stated that his object was to see the boy and provide him with money to enable him to go abroad. The mother said that she and her husband were old, and objected to their son going away, but on the 25th Taylerson saw the boy at his lodgings, and promised to provide him with all necessaries if he would go to America, to give him £15 on his arrival there, and £1 a week if he failed to get work, adding, "the reason is that we want you not to give evidence against you know who." It was arranged that the boy and the defendant should meet at a public-house in Tottenham-court-coad for the purpose of proceedings to Liverpool that night, and in the meantime Alliss informed Inspector Abberline of that fact, and by direction kept the appointment. The two were followed by the police to the Marlborough Head public-house, opposite the police-court and Mr. Newton's offices; and Mr. Newton and Mr. de Galla were observed standing close by. On seeing the inspector they walked away in different directions, and Taylerson, on being spoken to, refused to answer questions. The boy was then reconducted back to his lodgings by the police. On the 27th of September the solicitor to the Treasury received a letter from Mr. Newton complaining that Alliss had been kept in a state of duress, had been threatened by the police, and that he had been insructed by his parents to remove him from his objectionable surroundings and send him abroad. He said that the boy was most anxious to get away, and asked for an appointment on the part of the Treasury to meet the father. The statements with regard to the police and the boy's desire were certainly untrue, and he (the learned counsel) was obliged to allege that the letter was written either as a cloak to cover the proceedings of the previous day, or else in the interest of some other persons, instead of the lad's parents. An answer was sent denying the allegations, and statement that anyone trying to remove the lad in order to defeat the ends of justice would incur a great responsibility. After some further correspondence information came to the authorities which led them to suppose that these efforts to remove Alliss were being made really in the interest of Lord Arthur Somerset, whose name had come into the case in the course of the investigation, and against whom on the 12th of November a warrant was obtained. Almost immediately afterwards negotiations were renewed by Mr. Newton, ostensibly on the part of Alliss's father, for an interview with his son, and an arrangement was made to meet at the Treasury. The father, however, had said he was too poor to come to London, and Mr. Newton sent him the money to enable him to keep the appointment. On the father's arrival the son positively declined to see him, so he had to go away. On the 6th of December, the warrants against Lord Arthur Somerset and Hammond not having been executed owing to those persons having left the country, the boys Wright, Perkins, Swinskull [i.e. Swinscow], and Thickbroom were dismissed from the Post Office. On the 9th, in consequence of a communication they received, Perkins and Thickbroom met Mr. Newton at the corner of Oxford-street and Poland-street. He reminded them that it was he who had cross-examined them at the police-court, and told them that he knew someone who was prepared to help them, and that if they liked to go to Australia they should be provided with an outfit, a sum of £20, and £1 a week for three years, adding that two or three lads had gone away and were doing very well. He asked them to get Wright, Swinskull, and Barber to meet him on the following day at one o'clock, and observed that Alliss had made a great fool of himself. He sent them 10s. to pay Barber's fare from home, and next day Wright, Swinskull, and Perkins kept the appointment, the other two being absent. De Galla met thm, and told them they were to start that night for Dover, and suggested that they should write to their parents saying that they should not return home. He subsequently informed them that the boat for that night was full, and that he would find them lodgings for the night. He conducted them to a coffee-house in the Edgware-road, gave them a sovereign to pay expenses, told them to say indoors until half-past-nine to see whether Thickbroom came, and to give fictitious names. On the 11th of December he called, and finding that Thickbroom had not arrived, eventually told the boys that they had better go home, as there was some difficulty about obtaining their parents' consent. It was only conjecture, but some light was thrown upon this change of plans from the fact that Swinskull's parents had communicated with the police immediately upon receiving his letter. Upon proof of the statement he (the learned counsel) had laid before the court, he should ask the magistrate to come to the conclusion that the three defendants, acting independently it was true, had for their object the prevention of evidence being given against either Hammond or Lord Arthur Somerset or other persons, and that, therefore, they were endeavouring to defeat the ends of justice, as stated in the summons. He regretted to find among them a member of the legal profession, whose name was so well known, and trusted that it would turn out that nothing more than excessive zeal on behalf of his clients had led him into what he must have known was a serious infraction of the law.

Mr. Gill suggested that, as the cross-examination of witnesses must occupy some time, it would be better to adjourn at this point until a day when the magistrate would be able to devote his whole attention to the case.

Mr. Wontner supported the appeal, on the ground that he had only just been instructed, and had not had time to prepare his case.

Mr. Gill observed that he was quite prepared to give a complete answer to the charge, but the case must be fully gone into, and much time would necessarily be occcupied.

The Magistrate – Will one day suffice?

Mr. Gill – Oh, no, sir: I should say at least three days.

Mr. Avory was also of opinion that it would occupy that length of time.

Eventually the hearing was adjourned until next Monday week, Mr. Gill observing that it had been stated by one journal that his client assisted Hammond to escape, whereas that person had left the country before Mr. Newton came into the case. (Morning Post)

2 January 1890

THE CLEVELAND STREET SCANDAL.

LONDON, Jan. 2. – Sir Charles Russell has given up his brief for Lord Euston in the libel action regarding the Cleveland street scandal, and accepted one from the Prince of Wales. He will watch the case in the interest of Albert Victor of Wales, whose name has been persistently dragged into the affair. (Goshen Daily News, Indiana)

7 January 1890

THE CLEVELAND-STREET CASE.

At Bow-street Police-court yesterday Mr. Arthur Newton, solicitor, of Great Marlborough-street, Mr. F. Taylerson, his articled clerk, and Adolphus de Gallo, interpreter, appeared to adjourned summonses, charging them with having between September 25 and Dcember 12, conspired together with other persons to obstruct and defeat the due course of law and justice in respect to legal proceedings instituted against certain persons for offences commimtted at 19, Cleveland-street, Fitzroy-square.

Mr. Horace Avory, instructed by Sir A. K. Stephenson, solicitor to the Treasury, conducted the prosecution; Mr. Gill, barrister, defended Mr. Newton, and Mr. St. John Wontner appeared for the other defendants.

Mr. Avory, having, on the previous occasion, opened the case at some length, now proceeded to call evidence.

Illustration from Police Gazette Algernon Edward Allies, a youth whose parents reside at Sudbury, deposed that on 4th September last he gave evidence at the Marlborough-street Police-court against Newlove and Veck, who were charged in connection with the Cleveland-street case, and was bound over to appear against them at the Old Bailey. Between those periods he was living in lodgings under the observation of the police. About the 23rd August, Constable Hanks took a statement from him at Sudbury; but two days prior to that date he had received an anonymous letter. He did not know the handwriting; but in consequence of that communication he destroyed a number of letters he had in his possession from Lord Arthur Somerset. In his evidence at the Police-court he referred to an individual who was known as Mr. Brown, at the house in Cleveland-street, and described his personal appearance. That individual was Lord Arthur Somerset. After he had given evidence at the Old Bailey he returned to his lodgings in Houndsditch. There the defendant Taylerson called upon him, and suggested that he should go to America, promising to hand the captain of the ship he went in £15 for him on his arrival, and to allow him £1 a week if he failed to obtain work. After some persuasion he agreed to go, and an appointment was made for that evening at the A 1 public-house in Tottenham-court-road. In the course of conversation Taylerson said that no doubt he (witness) could guess whom he came from. He (witness) supposed that he meant Lord Arthur Somerset, but afterwards he believed Taylerson said he came from Mr. Newton, and gave him 6s. to buy some shirts. After Taylerson left him, he communicated with Inspector Abberline, and by his direction kept the appointment, being followed by that officer and Constable Hanks. On meeting Taylerson he was taken by him to the Marlborough Head public-house, in Great Marlborough-street, and there Inspector Abberline demanded of Taylerson what he was doing with that boy. He declined to answer, and he (witness) was then handed over to the care of Cosntable Hanks. He had never told his parents or any one else that he was kept in a state of terror by the threats of the police, or that they neglected to provide him with clothes, or that he was anxious to get away. The only remark he had ever made about the matter was that he was very comfortable. He had never expressed any anxiety to see his father, and when he was brought to the Treasury for that purpose he declined the interview.

Cross-examined by Mr. Gill – There was no reason why he should fear his father. He lived at the house in Cleveland-street for some months after Christmas, 1888. Previous that that he had been convicted of stealing from a club, and was discharged without punishment, on Lord Arthur Somerset's becoming surety for his good behaviour. That gentleman had frequently promised to give him a start in life, and in August he appealed to him to obtain for him a situation in a tobacconist's shop. When Constable Hanks called on him at Sudbury he was somewhat frightened at first, as he thought he was going to be imprisoned, and he preferred being a witness to being a prisoner. Until the 12th of November he swore no information against Lord Arthur Somerset. He was not ordered by the police not to communicate with his parents, and they were not told at first that any letter for hiim must come through Inspector Abberline, though that was done eventually. He was not supplied by the police with clothes and money, but all his expenses were paid. The police did not tell him the very words to put in his letters to his parents and other people. He declined to state the address from which some of his letters were written, as that was his present address. He referrred the learned counsel to Inspector Abberline for the information.

After some discussion between the legal gentlemen engaged in the case, the magistrate decided that the question should not be pressed.