It should break any civilized person's heart that Peter's Mom was murdered and the final horror he was blamed for the crime. The one comfort and, I hope Peter realizes this, a lot of people care about him and wish him only the best.

And that he has a lot of friends that he never met. Maybe someday he will.

FREEDOM

OF INFORMATION COMMISSION

OF THE STATE OF CONNECTICUT

| In the Matter of a Complaint by |

FINAL DECISION |

Ruth Epstein and

The Lakeville Journal Company, LLC,

|

|

|

|

Complainants |

|

| |

against

|

|

Docket #FIC 2003-320 |

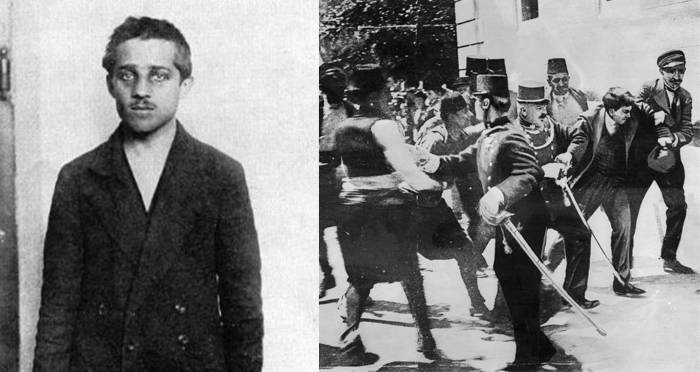

State of Connecticut,

Department of Public Safety,

Division of State Police

|

|

|

|

Respondents |

September 2, 2004 |

| |

|

|

|

The above-captioned matter was

heard as a contested case on January 22, 2004, at which time the complainants

and the respondent appeared, stipulated to certain facts and presented

testimony, exhibits and argument on the complaint. This case was consolidated

for hearing with docket #FIC 2003-313, Donald S. Connery v. State of

Connecticut, Department of Public Safety, Division of State Police.

After consideration of the entire record, the

following facts are found and conclusions of law are reached:

1. The respondent is a public

agency within the meaning of §1-200(1), G.S.

2. By letter of complaint filed

September 8, 2003, the complainants appealed to the Commission, alleging that

the respondent violated the Freedom of Information (“FOI”) Act by denying their

request for records of the homicide of Barbara Gibbons. That case is commonly known as the Peter

Reilly case, because of the conviction, ultimately set aside in 1977, of

the victim’s teenaged son in 1974.

3. It is found that by letter dated June 26,

2003 the complainants requested the complete state police file on the

Barbara Gibbons homicide case, from September 28, 1973 to the present.

Specifically, the complainants indicated that the records in the file “should

include, but not be limited to, all data on the original investigation, led by

Lt. James Shay, that resulted in the manslaughter conviction of Peter Reilly on

April 12, 1974; and all data on the reinvestigation in 1976-77, as requested by

Governor Ella Grasso and led by Captain Thomas McDonnell, following the vacating

of Reilly’s conviction.”

4. It is found that the respondent replied by

letter dated July 1, 2003 that the complainants’ request had been received, and

then by letter dated August 28, 2003 denied the request on the grounds that the

investigation was still pending and that the records were exempt from disclosure

pursuant to §1-210(b)(3), G.S.

5. It is further found that, by letter dated

November 28, 2003, the respondent added that “upon further review of this matter

… determined that pursuant to C.G.S. Sec. 1-215 and 54-142a, there is no public

record in response to your request.”

6. The respondent maintains that there are no

public records responsive to the complainant’s request, and that the Commission

therefore lacks jurisdiction over the complaint, pursuant to §§54-142a(a) and

1-215(a), G.S.

7. Section 54-142a(a), G.S., provides in

relevant part:

Whenever in any criminal case, on

or after October 1, 1969, the accused, by a final judgment, is found not guilty

of the charge or the charge is dismissed, all police and court records and

records of any state's attorney pertaining to such charge shall be erased upon

the expiration of the time to file a writ of error or take an appeal, if an

appeal is not taken, or upon final determination of the appeal sustaining a

finding of not guilty or a dismissal, if an appeal is taken….

8. Section 54-142a(e), G.S.,

provides in relevant part:

…any law enforcement agency

having information contained in such erased records shall not disclose to

anyone, except the subject of the record …information pertaining to any charge

erased under any provision of this section….

9. With respect to disclosure to

the subject of the record, §54-142a(f), G.S., provides in relevant part:

Upon motion properly

brought, the court or a judge thereof, if such court is not in session, may

order disclosure of such records (1) to a defendant in an action for false

arrest arising out of the proceedings so erased ….

10. Section 54-142c(a), G.S.,

provides in relevant part:

…any criminal justice agency

having information contained in such erased records shall not disclose to anyone

the existence of such erased record or information.

11. It is concluded that erasure

does not mean the physical destruction of records. Rather it involves sealing

the files and segregating them from materials that have not been erased and

protecting them from disclosure. State v. Anonymous, 237 Conn. 501, 513

(1996)

12. Section 1-215(a), G.S.

provides in relevant part:

Notwithstanding any provision of

the general statutes to the contrary, and except as otherwise provided in this

section, any record of the arrest of any person, other than a juvenile, except a

record erased pursuant to chapter 961a, shall be a public record from the time

of such arrest and shall be disclosed in accordance with the provisions of

section 1-212 and subsection (a) of section 1-210, except that disclosure of

data or information other than that set forth in subdivision (1) of subsection

(b) of this section shall be subject to the provisions of subdivision (3) of

subsection (b) of section 1-210.

13. Section 1-215(b), G.S., provides:

For the purposes of this section,

“record of the arrest” means (1) the name and address of the person arrested,

the date, time and place of the arrest and the offense for which the person was

arrested, and (2) at least one of the following, designated by the law

enforcement agency: The arrest report, incident report, news release or other

similar report of the arrest of a person.

14. Section 1-200(5), G.S.,

provides:

“Public records or files” means

any recorded data or information relating to the conduct of the public's

business prepared, owned, used, received or retained by a public agency, or to

which a public agency is entitled to receive a copy by law or contract under

section 1-218, whether such data or information be handwritten, typed,

tape-recorded, printed, photostated, photographed or recorded by any other

method.

15. Section 1-210(a), G.S., provides in relevant

part:

Except as otherwise provided by

any federal law or state statute, all records maintained or kept on file by any

public agency, whether or not such records are required by any law or by any

rule or regulation, shall be public records and every person shall have the

right to (1) inspect such records promptly during regular office or business

hours, (2) copy such records in accordance with subsection (g) of section 1-212,

or (3) receive a copy of such records in accordance with section 1-212.

16. The respondent maintains that

§1-215(a), G.S., provides that any erased record is not a public record.

17. It is concluded, however, that §1-215(a),

G.S., by its terms specifically applies only to the limited information

contained in a “record of arrest,” not to all erased records.

18. It is therefore concluded that the

Commission has jurisdiction to determine whether records have been erased, and

whether erased records are exempt from disclosure.

19. It is found that requested records are

public records within the meaning of §§1-200(5) and 1-210(a), G.S.

20. It is found that Barbara Gibbons was killed

in the home she shared with her son, Peter Reilly, an 18-year-old high school

senior.

21. It is found that Reilly, who had arrived at

home that night after a teen center meeting, reported the crime in a series of

telephone calls for medical assistance.

22. It is found that Reilly was taken into

custody and interrogated, made certain confessions, and was placed under arrest

for the crime of murder.

23. It is found that, after a lengthy jury

trial, Reilly was found guilty of the crime of manslaughter in the first degree

on April 12, 1974.

24. It is found that Reilly subsequently

petitioned for a new trial on the grounds of newly discovered evidence.

25. It is found that a new trial was granted on

March 25, 1976. Reilly v. State, 32 Conn. Sup. 349 (1976) (Speziale,

J.) In his memorandum of decision, Judge Speziale, who had also presided over

the original trial, concluded that, “After a long and deliberate study of all of

the transcripts of the original trial and the instant proceeding, together with

the pleading and exhibits in both cases, this court concludes that an injustice

has been done and that the result of a new trial would probably be different.”

Reilly v. State, at 356-57.

26. It is found that, on November 24, 1976,

Judge Maurice Sponzo dismissed the charges against Reilly, after State’s

Attorney Dennis A. Santore determined not to prosecute Reilly for the Gibbons

homicide.

27. It is found that on November 26, 1976,

Governor Ella Grasso ordered the respondent to reinvestigate the Gibbons

homicide, and asked Chief State’s Attorney Joseph Gormley to see if there had been misdeeds in the

case by police or prosecutors.

28. It is found that on December

23, 1976, three days after Gormley reported that he had found nothing improper

in the police and prosecution actions, Judge Speziale named a one-man grand jury

to investigate possible crimes by the state in the handling of the Gibbons

homicide. Judge Maurice Sponzo was appointed to conduct the inquiry, with the

assistance of Paul McQuillan as special state’s attorney.

29. It is found that on June 1, 1977, Judge

Sponzo’s report of his findings concluded that no crimes were committed by

police or prosecutors, but he severely criticized the state’s handling of the

case. Eliminating Peter Reilly as a suspect, Sponzo’s secret addendum to his

report named five persons as suspects worthy of investigation.

30. It is found that on September 28, 1977,

Captain Thomas J. McDonnell, the detective division commander who led the state

police reinvestigation ordered by Governor Grasso, issued his 58-page report.

Eliminating all other suspects, he came to “the inescapable conclusion” that

Peter Reilly “is, in fact, the sole perpetrator in the Barbara Gibbons

homicide.”

31. It is found that on November 22, 1977, Judge

Sponzo added the words “with prejudice” to the dismissal of the manslaughter

charges against Reilly ordered a year previously.

32. It is found that on June 2, 1978, Governor

Grasso authorized a $20,000 reward for information leading to the solution of

the Gibbons homicide, but no individuals were subsequently charged with the

crime.

33. It is found that the police and court

records of the Gibbons homicide as they pertain solely to the charges against

Mr. Reilly were erased by operation of law no later than 1978.

34. The complainants maintain that given the

heightened public interest in the Reilly case, and continuing assertions since

1980 by present and former state police officials and employees of Reilly’s

guilt, the records should be disclosed so that the public may know whether the

respondent conducted its investigation and prosecution properly.

35. The complainants additionally maintain that

the requested records must be disclosed because they were disclosed, at least in

part, to a reporter sometime in 1988.

36. While it appears that a redacted disclosure

was in fact made to a reporter at the Lakeville Journal who was writing an

anniversary story at the time, it is concluded that the erasure statutes contain

no provisions for waiver, and that such a disclosure would not affect the status

of the records as erased.

37. On February 19, 2004 the

Commission received what appears to be an affidavit of Peter Reilly, stating his

desire that the requested records be disclosed, and waiving any privacy rights

that he might have.

38. However, Mr. Reilly is not a party to this

case, nor has he requested to be made one. Nor did any party offer Mr. Reilly’s

affidavit into evidence. The affidavit is therefore not properly before the

Commission. Even if it were, the erasure statutes have been interpreted by the

Supreme Court to mean that the blanket prohibition against disclosure also

applies to the person who was the defendant in the criminal case, and that the

erasure provisions may not be waived by him. Lechner v. Holmberg, 165

Conn. 152, 161-62 (1973); State v. West, 192 Conn. 488, 495-96 (1984).

39. It is concluded that the

respondent did not violate §1-210(a), G.S., when it failed to provide copy of

erased records that pertained solely to the dismissed charges against Mr.

Reilly.

40. However, the complainants

maintain that, even if the records pertaining solely to Mr. Reilly have properly

been erased, not all of the records of the Gibbons homicide pertain to Mr.

Reilly, and that the records that do not pertain to Mr. Reilly are not erased by

operation of §54-142a(a), G.S.

41. Based in part on the grand

jury report described in paragraph 29, above, it is found that some of the

records maintained by the respondent pertain to an investigation of the

respondent’s conduct, separate and distinct from records pertaining to Mr.

Reilly that are subject to erasure, and that some of the records also pertain to

five other individuals deemed worthy of investigation.

42. The language of §54-142a,

G.S., does not define the phrase “records … pertaining to such charge” that are

to be erased. Specifically, the statute does not address the status of records

that pertain to suspects and subjects other than the accused.

43. With respect to the erasure

statute, the Supreme Court has stated that it should be construed to give it the

“legal and practical effect” intended by its drafters, as revealed by the

legislative history. Cislo v. Shelton, 240 Conn. 590, 608 (1997).

44. In State v. Anonymous,

237 Conn. 501, 516 (1996), the Supreme Court observed that the fundamental

purpose of the records erasure and destruction scheme embodied in §54-142,

G.S., is to “erect a protective shield of presumptive privacy for one whose

criminal charges have been dismissed.” The purpose of the erasure statute is to

protect innocent persons from the harmful consequences of a criminal charge

which is subsequently dismissed.

45. In Cislo v. Shelton,

240 Conn. 590 (1997), the Supreme Court further indicated the central function

of the erasure statute. Specifically, the court observed that the legal effect

of erasure, as specified by a 1967 amendment (P.A. 67-181) to §54-90, G.S., is

such that “[n]o person who shall have been the subject of such an erasure order

shall be deemed to have been arrested ab initio ….” Cislo v. Shelton,

supra at 600-601. Later legislative debate in 1974 demonstrated that the

legislature primarily intended to reinforce the ability of those persons whose

records had been erased after a nolle to state that, with respect to those

erased charges, they had never been arrested. Id. at 604-605.

46. It is found that, given the

extensive publicity surrounding Barbara Gibbons’ death, it would appear to be of

little comfort to Mr. Reilly to be able to declare, because of the erasure

statutes, that he was never arrested for the crime.

47. In Pascal v. Pascal, 2

Conn. App. 472, 484-85 (1984) the Appellate Court observed: “The beneficiaries

of the provisions of General Statutes §54-142a are “only the accused in criminal

cases …. The erasure of criminal records demanded by [that statute] is a

personal right of the accused only.” (citing McCarthy v. FOIC, 35 Conn.

Sup. 186, 193 (1979).)

48. In McCarthy v. FOIC,

supra, the Superior Court (Bieluch, J.) held that the coverage of

§54-142a, G.S., cannot be extended collaterally to records of complaints and

disciplinary proceedings involving police officers associated with erased

criminal cases.

49. It is concluded that records

used to investigate the conduct of the respondent and its employees, and records

pertaining to other persons who either were or should have been investigated as

suspects in the crime of which Mr. Reilly was accused, are not shielded by the

provisions of §54-142a, G.S.

50. It is found that the

legislative purpose of the erasure statutes is clearly not served by shielding

from public view information that might tend to implicate others in the crime of

which the accused was acquitted, or that might cast light on the respondent’s

investigation of the homicide, all without providing any functional protection

to the accused.

51. The U.S. Supreme Court has

observed, with respect to the federal counterpart to the FOI Act, that the

purpose of that FOI Act is to shed light “on an agency’s performance of its

statutory duties.” The statute is a commitment to “the principle that a

democracy cannot function unless the people are permitted to know what their

government is up to.” The statute’s “central purpose is to ensure that the

Government’s activities be opened to the sharp eye of public scrutiny.” U.S.

Department of Justice v. Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, 489

U.S. 749, 772-774 (1989).

52. It is found that the result

of erasure of records of the Barbara Gibbons homicide not pertaining to Mr.

Reilly would be to support the respondent’s oft-repeated contention that Mr.

Reilly is the actual killer, to prevent any possibility of bringing forth

evidence that might exonerate Mr. Reilly, to frustrate the public’s legitimate

public interest in the controversy, and to protect the identity of other

individuals who might have been but were not charged with the crime. Such a

result is directly contrary to a fundamental maxim of statutory

construction:

“The law favors rational and

sensible statutory construction…. The unreasonableness of the result obtained

by the acceptance of one possible alternative interpretation of an act is a

reason for rejecting that interpretation in favor of another which would provide

a result that is reasonable…. When two constructions are possible, courts will

adopt the one which makes the [statute] effective and workable, and not one

which leads to difficult and possible bizarre results.

Maciejewski v. West Hartford, 194 Conn. 139, 151-52

(1984).

53. It is therefore concluded that records that do

not pertain solely to Mr. Reilly, but rather pertain to an investigation of the

respondent’s conduct and the respondent’s investigation of other individuals,

are not erased by the operation of §54-142a, G.S.

54. It is therefore concluded that the

respondent violated §1-210(a), G.S., when it denied the existence of, and

refused to provide copies, of records of the Barbara Gibbons homicide that do

not pertain to the charges against Mr. Reilly, but rather pertain to an

investigation of the respondent’s conduct and the respondent’s investigation of

other individuals.

The following order by the Commission is hereby

recommended on the basis of the record concerning the above-captioned

complaint:

1. The respondent shall forthwith provide to the

complainants copies of records of the Barbara Gibbons homicide that do not

solely pertain to the charges against Mr. Reilly. Such disclosed records shall

include any records investigating, or used to investigate, the conduct of the

respondent, and any records of the respondent’s investigation of inviduals other

than Mr. Reilly.

Approved by Order of the Freedom

of Information Commission at its special meeting of September 2, 2004.

___________________________________

Petrea A. Jones

Acting Clerk of the Commission

PURSUANT TO SECTION 4-180(c), G.S., THE FOLLOWING ARE THE

NAMES OF EACH PARTY AND THE MOST RECENT MAILING ADDRESS, PROVIDED TO THE FREEDOM

OF INFORMATION COMMISSION, OF THE PARTIES OR THEIR AUTHORIZED

REPRESENTATIVE.

THE PARTIES TO THIS CONTESTED CASE ARE:

Ruth Epstein and

The Lakeville Journal Company, LLC

c/o Alan Neigher, Esq.

1804 Post Road East

Westport, CT 06880

State of Connecticut,

Department of Public Safety,

Division of State Police

c/o Stephen R. Sarnoski, Esq.

Assistant Attorney General

110 Sherman Street

Hartford, CT 06105

___________________________________

Petrea A. Jones

Acting Clerk of the Commission

From the Hartford Courant

The small towns in Litchfield County rose to Peter Reilly's defense. To his friends and neighbors, his innocence was obvious.

Peter was amiable and law-abiding. They could not fathom how a dubious confession, obtained by high-pressure psychological persuasion, could triumph over the absence of evidence. Lt. James Shay and his investigators had to know Peter had no time to commit the crime — and no motive. The medical findings suggested at least two attackers.

Bake sales and other efforts raised $60,000 to free Peter on bond for the appeal. The convicted killer was welcomed back at his high school to complete his senior year. Roxbury playwright Arthur Miller organized a powerful rescue party — a new attorney, a crack investigator, the nation's leading forensic pathologist and a top expert on mind control.

Superb reporting by The Hartford Courant's Joseph A. O'Brien and critical editorials in the Lakeville Journal raised alarming questions about the state police investigation. The case became a national sensation.

After a long hearing for a new trial in 1976, Superior Court Judge John A. Speziale, the future state chief justice, declared that a "grave injustice" occurred in his courtroom two years earlier. State's Attorney John Bianchi dropped dead on a golf course before deciding to risk a second trial. His successor, Dennis Santore, discovered a time bomb: a critical document, never revealed to the defense or the court, placing Peter five miles away at the time the state claimed he was home killing his mother.

Astonishing events followed Peter's exoneration. A one-man grand jury investigation in 1977 condemned law enforcement's actions. A simultaneous nine-month state police reinvestigation, ordered by Gov. Grasso and led by Capt. Thomas McDonnell, reached an "inescapable conclusion" naming the "sole perpetrator" in the Barbara Gibbons killing — Peter Reilly.

Knowing that their conclusion would set off fireworks, the police sought public support by leaking their 58-page, confidential report before giving it to the governor.

"New Police Report Calls Reilly Slayer" was one headline regarding a bizarre new theory. Supposedly, upon arriving home, Peter backed his car over his mother. He then dragged her broken body into the bedroom to start his killing spree.

Gov. Grasso's legal counsel, Paul McQuillan, who was the prosecutor for Judge Maurice Sponzo's grand jury, was appalled by this monument of disinformation. Knowing that I spent three years on a just-finished book on the case, he gave me a copy of the secret police report. "Read it," he said. "Then do whatever you think best."

I was being used — the governor needed public support before taking on the state police — but I felt a need to act. At a Hartford press conference, I described the report's dozens of errors, denounced the rampant speculation, described the reinvestigation as a giant scam and called for the resignation or firing of the state police commissioner, Edward P. Leonard.

More important, State's Attorney Santore rejected the police report as "contrived," "unworthy" and "blatantly contradictory." The car theory was "completely untenable." He considered arresting Leonard.

The governor called Leonard in and he withdrew the McDonnell report. He resigned a few months later, but during a farewell tour of police barracks he told troopers it was about politics and public opinion, not mistakes. Thereafter, for decades, the department's answer to press inquiries about the Gibbons murder was, "We are satisfied with the result of our original investigation."

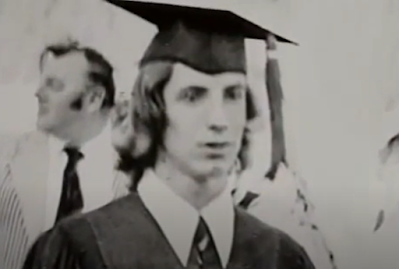

Actor Paul Clemens, who played Peter in the TV Movie, Author Joan Barthel who fought for Peter's Freedom and wrote the book, "A Death in Canaan" and Peter Reilly. www.corbisimages.com

Thinking Analytically

Though it may sound trite, I remember reading Sherlock Holmes Stories as kid, their logic has stayed with me ever since. Having a critical mind, always looking for the real truth matters to me.

Colonel Ross still wore an expression which showed the poor opinion which he had formed of my companion's ability, but I saw by the inspector's face that his attention had been keenly aroused.

"You consider that to be important?" he [Inspector Gregory] asked.

"Exceedingly so."

"Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?"

"To

the curious incident of the dog in the night-time."

"The dog did nothing in the night-time."

"That was the curious incident," remarked Sherlock Holmes.

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1893)

Inspector Gregory and Sherlock Holmes in "Silver Blaze" (Doubleday p. 346-7)

When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever...

"You will not apply my precept," he said, shaking his head. "How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth? We know that he did not come through the door, the window, or the chimney. We also know that he could not have been concealed in the room, as there is no concealment possible. When, then, did he come?"

The Sign of the Four, ch. 6 (1890)

Sherlock Holmes in

The Sign of the Four (Doubleday p. 111)

I read a book which is claimed by some, me included, to be the best mystery ever written. I read it when I was 10-years-old. Elizabeth Macintosh wrote "The Daughter of Time" under the pen name Josephine Tey. It is the story of an injured Scotland Yard Inspector, who is recovering in the hospital and needs something to occupy his time. He comes across a picture of King Richard III. Something troubling occurs to him, this man does not look like a murderer, much less the killer of his two nephews, twelve-year-old King Edward V and his 10-year-old brother Richard Duke of York. He is driven to find the truth. When he does, he is perplexed by the fact that so many people could be so wrong.

The Guardian Newspaper(UK) ranked it second all time:

2. The Daughter of Time by Josephine Tey

Inspector Grant spends the entire book in a hospital bed, the murders happened more than 500 years ago, and you'd get more graphic violence in the phone book. To stop himself going nuts with boredom, and because Richard III's face interests him, Grant starts investigating who really killed the Princes in the Tower. The results aren't exactly what he expected. It's a fascinating piece of research that raises all kinds of questions about the accuracy of "history" but that never gets in the way of the fact that it's a beautifully constructed mystery.

It is predicated upon the premise, that what history records as the truth, isn't necessarily the truth.

On its publication Anthony Boucher called the book "one of the permanent classics in the detective field.... one of the best, not of the year, but of all time".

Dorothy B. Hughes also praised it, saying it is "not only one of the most important mysteries of the year, but of all years of mystery".

This book was voted number one in The Top 100 Crime Novels of All Time list by the UK Crime Writers' Association in 1990.

Winston Churchill stated in his History of the English-Speaking Peoples his belief in Richard's guilt of the murder of the princes, adding, "It will take many ingenious books to raise the issue to the dignity of a historical controversy", probably referring specifically to Josephine Tey's novel, "The Daughter of Time" published seven years earlier. The papers of Sir Alan Lascelles contain a reference to his conversation with Churchill about the book.

In 2012, Peter Hitchens wrote that The Daughter of Time was "one of the most important books ever written".